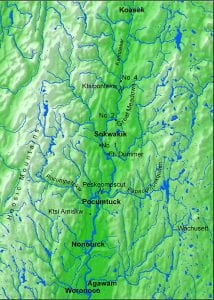

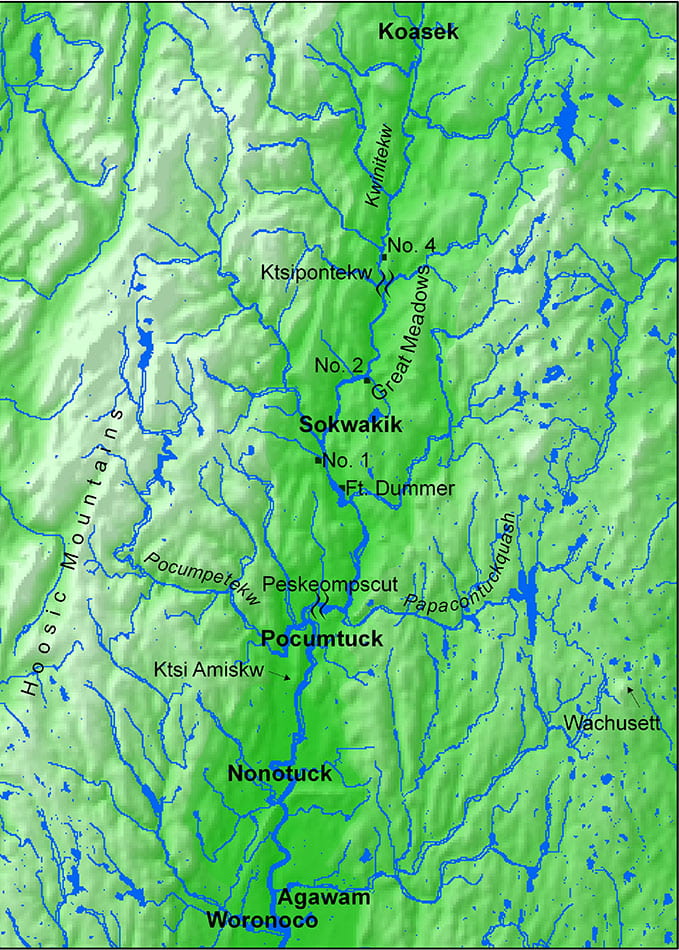

I’d like to begin by acknowledging that we stand on Nonotuck land. I’d also like to acknowledge our neighboring Indigenous nations: the Nipmuc and the Wampanoag to the East, the Mohegan and Pequot to the South, the Mohican to the West, and the Abenaki to the North.

In my first few years at Amherst, I could go days or even weeks without leaving campus, perhaps walking to Antonio’s for a slice of pizza or driving to Staples for school supplies. My off-campus social excursions were even more limited than my physical ones; I had few meaningful interactions with members of the local community and the majority of my social contacts were other Amherst students. Like many Amherst students, I existed inside a socio-cultural college bubble that resulted in little overall engagement with the broader regional culture and history of the Connecticut River Valley. Over the past year, I have experienced the other side of that separation; the invisible walls of COVID-19 protocols have created a physical bubble around the campus in addition to the sociological one, and as a remote student I have felt dislocated from the campus since we were sent home more than a year ago in March 2020. This experience, difficult on many levels, has challenged me to look more critically at how I and Amherst College as a community have existed and should exist within our space in the Connecticut River Valley. In particular, I have been thinking a lot about the ways in which this insularity creates barriers that separate us from the history and culture of the land. At the Racial History of Amherst project, we seek to center the land that Amherst occupies as an investigation into race and our roots, and a crucial first step in that process involves a deeper and more honest acknowledgment of the role of the College in carrying out violent erasures of local Native peoples.

The insularity of Amherst College, in addition to creating social barriers between us and the local community, has contributed to the erasure of the violent history of the land upon which we stand and in particular the long arc of College-affiliated participation in perpetuating that violence against Native communities. The College has made some token gestures towards acknowledging this past but has failed to recognize the broader history of how many members of the Amherst community beyond Lord Jeffrey Amherst have participated in violence against Native people. Through the Racial History of Amherst project, we seek to bring that history to light and provide opportunities to engage with it so that we as individuals and a College can acknowledge this shameful reality and challenge the effects that still manifest in the present.

All Amherst students now know the history of Lord Jeffery Amherst and how he advocated for biological warfare against Native communities. However, Jeffrey Amherst is just one of a long string of Amherst College-affiliated purveyors of physical and intellectual violence against Native communities. Famous figures from Amherst history such as Edward “Old Doc” Hitchcock Jr. – the son of the third president of the College and an 1849 graduate who himself served as Dean, physician, professor of Hygiene & Physical Education, and collector of College history from 1861-1911 – and William Fowler – a professor of Rhetoric & Oratory from 1838-1843 – both helped perpetuate violence and erasure against local Native people through their academic work. Athropologist Margaret Bruchac highlights how these academics perpetuated harmful myths against Native communities in their work and “contributed to the disconnection of local Native history as they systematically disinterred graves, disarticulated bodies, separated grave foods from gravesites, and traded desirable collections around the region” (Bruchac, “Native Presence in Nonotuck and Northampton,” 20).

Hitchcock Jr., whose name several fields, fellowships, and buildings now bear at the College now bear, forcibly disconnected Native objects from their locations and culture of origin for use in his Gilbert Museum of Indian Relics, which he donated to Amherst in 1853 (Bruchac, “Lost and Found,” 140). He waged violence and disrespect towards the remains and culture of these Native people by seizing them for display and failed to keep proper records of their origins, making it near-impossible to return them to their proper sites today (Bruchac, “Lost and Found,” 141). Amherst College housed stolen Native skeletal remains until the early 1970’s and similarly contributed to their further dislocation through a lack of caretaking or recording of origin data (Bruchac, “Lost and Found,” 141). This history, as elucidated in Bruchac’s series of excellent works on local Native history, is just one example of the deeper involvement of Amherst folks in the historical erasure and misrepresentation of Native peoples (see below for further reading from Bruchac). It is important to note that all of the remains once held at Amherst have been repatriated, the result of a long and laborious effort which involved multiple partners from the Five Colleges and the local nations’ Tribal Historical Preservation Offices.

The College has made some very initial steps towards recognizing the role of College affiliates in perpetuating various forms of violence against Native people, including the removal of the informal Lord Jeff mascot. However, these initial efforts are just the beginning of a long process in which the College must acknowledge this broader history of anti-Native action and seek to dismantle its effects. As a first step towards acknowledging and facilitating engagement with this history, we have begun to compile an Indigenous Resources page on the Racial History of Amherst site. While this list is by no means exhaustive, it provides background information and suggested readings on the history of local Native people as a starting point. Throughout the semester and beyond, we hope to add to this page to help provide further resources on this history. However, this type of background is just a starting point. As pandemic restrictions ease over the coming semesters, we hope to help facilitate the breaking of the other bubble – the socio-historical bubble that has often separated Amherst students from full engagement with the local community and history. Over the coming months, we seek to identify opportunities for student outings to regional sites that engage with Native history in the valley and beyond to promote awareness, education, and engagement from Amherst students. Throughout this process, we hope to incorporate the voices and input of Native Amherst students and Native people who reside in the area and center their experiences and perspectives.

The Racial History of Amherst project is not limited to just the College’s long-overdue 2020 Anti-Racism Plan, the 2016 removal of the Lord Jeff mascot, or the 2015 Amherst Uprising. The racial history of Amherst stretches beyond even the 200 years since our official founding, all the way back to the violent history of white supremacy and genocide waged against the Native people of the region, dating back to the arrival of the earliest colonists. Centering the land as this project seeks to do requires that we situate that land within our broader geographic context and this history that that geography entails. While the efforts of the project may be small in the face of the centuries of physical and intellectual violence waged by Amherst affiliates and other local people against Native communities, we hope that by providing opportunities for education, awareness, and actual engagement with this history, we as individuals and as a College community can take one small step towards dismantling the effects of that history. As we do so, we start to ask larger questions of ourselves and this history: By what other means has the College and/or its affiliates acted against Native communities throughout its history? By what forms can we best acknowledge this past and make it known to the community and the public? How do we center and amplify Native voices, experiences, and perspectives throughout this effort? What effects of Amherst College’s role in this past persist to the present, and what mechanisms can we use or create in order to start dismantling those impacts?

Claire Dunbar ’21

History & Psychology Major

Further Resources

For maps of the lands of the Native people in the region:

- Brooks, Lisa. (2008). “The Indigenous Northeast: a Network of Waterways.” The Common Pot. https://lbrooks.people.amherst.edu/thecommonpot/map1.html

For further reading on local Native presence, exploitative archeology, and the role of Amherst affiliates in perpetuating violence and dislocation:

- Bruchac, Margaret. (2004). “Native Presence in Nonotuck and Northampton.” In Kerry Buckley (Ed.), A Place Called Paradise: Culture and Community in Northampton, Massachusetts, 1654-2004, (pp. 18-38). Northampton, Massachusetts: Historic Northampton. https://repository.upenn.edu/anthro_papers/162/

- Bruchac, Margaret. (2010). “Lost and Found: NAGPRA, Scattered Relics, and Restorative Methodologies.” In Museum Anthropology, Vol. 33, Iss. 2, pp. 137–156. https://web.williams.edu/AnthSoc/native/Bruchac_MA_2010.pdf

Stolen Native remains and artifacts at Amherst College

- Catalogue of the Gilbert Museum of Indian Relics, 1903-2015: http://asteria.fivecolleges.edu/findaids/amherst/ma17.html

- Amherst College’s NAGPRA compliance documentation: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/12/21/2018-27707/notice-of-inventory-completion-beneski-museum-of-natural-history-amherst-college-amherst-ma

You must be logged in to post a comment.