This post is the first of a series on Israel Trask.

Last semester, I finally nailed down my thesis topic–the memorialization of slavery and Israel Trask in the archives–which of course involved describing it to numerous people. In so doing, I was surprised at just how many people didn’t know who Israel Trask was and how he connects to Amherst College. This post is thus intended as an introduction to the man and my thesis work.

So, who was Israel Trask? In brief, Israel E. Trask (1777-1835) was born in Brimfield, MA; owned several plantations in Mississippi and Louisiana; enslaved over 250 people; donated to the Amherst College Charity Fund; and served as a trustee from 1821 until his death in 1835. I first became aware of Trask in the days following the #ReclaimAmherst Campaign in the summer of 2020, but despite present appearances, Amherst has long benefited from and remembered the enslaver. In 1873, William S. Tyler offered a short biography of the man in his History of Amherst College During its First Half Century, 1821-1871, stating that though the exact “amount of Mr. Trask’s donation to the College is unknown… [d]oubtless he was a liberal donor to the College in all its great emergencies during the fifteen years of its history.” In 1950, Stanley King additionally stated in his A History of the Endowment of Amherst College that “the College relied on [Trask] in financial matters. …He was a member of the Board from 1821 to 1835, during which time he missed only one meeting of the Board.” While both men seem to have some knowledge of Trask’s personal background, his exact contributions to the College remain unclear.

This first post thus seeks to delineate Trask’s relationship to the College. Subsequent posts will focus on the lives of people he enslaved and his place in the broader landscape of slavery in the North. In the meantime, I highly recommend that you spend some time reading or listening to the Trask 250 series on genealogist Nicka Sewell-Smith’s website, Who is Nicka Smith? She will be visiting Amherst College in October.

The Financials

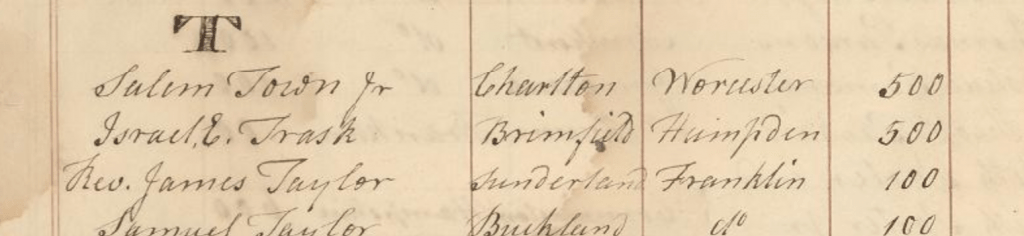

The most traceable connection between Trask and Amherst comes in the form of the former’s financial contributions. Israel Trask’s association with Amherst College appears to begin with his subscription to the Amherst College Charity Fund. Trask pledged $500, the upper end of amounts pledged (Joseph Estabrook of Amherst made the largest initial contribution at $1005), which has a relative inflated worth of $10,916.26 today. He later made a series of three interest payments in 1823, 1824, and 1826 amounting to an additional $210. Trask’s total financial contributions to the Charity Fund thus have a relative inflated worth of about $20,000.

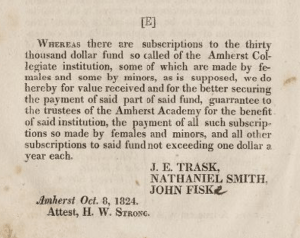

Trask’s connection to the Charity Fund does not end here. In 1824, the College was fighting to secure its charter and facing heavy opposition from Williams College. In preparation of intense financial scrutiny from the Massachusetts legislature and in response to the deaths of several of the bearers of the original guaranty bond, the College began a new $30,000 fund in 1822 as proof of its financial stability. However, the primary subscribers to the fund were women and minors and thus more easily challenged and discredited.*

This is where Trask comes in. Alluding to the fund and the legislative inquiry, an October 20, 1824 letter from then-president Heman Humphrey states that

The Agents of [Williams] College, continued to the very last, to work hard for their money. They attacked us in every possible way, but they were met at every point & defeated. I wish yo had been present, when your guarantee bond was read. It fell upon them like a clap of thunder & put them all in confusion. They complained that it was unfair; objected to it being read; it was two hours, I should think, before they recovered their composure. (Israel E. Trask Papers, Box 1, Folder 8)

Humphrey appears to be referencing this otherwise unremarkable paragraph in the Appendix to the Report of the Committee Appointed to Inquire into Facts Relative to the Amherst Collegiate Institution. Here, Trask (note that ‘I’ and ‘J’ were often considered interchangeable), in addition to Nathaniel Smith and John Fiske, pledged to cover the subscriptions made by women and minors. This would, in turn, squash any challenges against the fund and the charter by Williams. While it remains unclear if Trask paid out on this guarantee, it is clear that he was instrumental in helping to secure the charter.

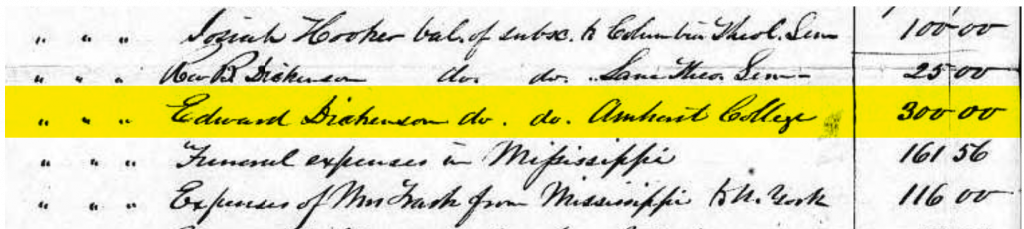

I have not yet gotten my hands on the Trustee Minutes that may indicate further financial ties to the College. However, Tyler notes that “there was an outstanding subscription of three hundred dollars to the College, which matured after his death in November and was paid by his executors.” A payment to Edward Dickinson, then Treasurer of Amherst College, is seen in Trask’s account papers in his will, accessible via Ancestry.com:

This makes for a known total of $1,010 paid to Amherst College by Israel Trask between 1818 and 1835. The same will contains a transfer of a $140,000 debt owed by his brother James for the LaGrange Plantation and the 150 people enslaved on it. Even while Amherst was admitting (a select few) Black students and Amherst students were campaigning for the abolition of slavery, trustee Israel E. Trask was profiting from the peculiar institution. That money then made it back to Amherst.

Other Contributions

In addition to these financial contributions, Trask influenced–or at least attempted to–academic life at the College. As a result of Trask’s patronage and connections, Jonas King was appointed the first Professor of Oriental Literature in 1821 through a meeting with Trask’s longtime friend and Amherst College financier Rufus Graves (see Rufus Graves to Israel E. Trask, August 3, 1821, Israel E. Trask Papers, Box 1, Folder 5) While King appears on the first and subsequent college catalogs, his appointment came with the expectation that he would first study in Europe for a period of several years. It does not appear that he ever taught at the College. More research is needed to determine other contributions to College life.

Trask’s papers have been at the Amherst College Archives and Special Collections since 1967, but it was not until 2017 that they were made into their own collection–the Israel E. Trask Papers. Deputy Archivist Chris Barber pulled the Trask materials out of the poorly-described Miscellaneous Manuscripts Collection and created a detailed finding aid for this material to make it easier to discover and use. In a single, unremarkable archival box is packed away letters describing the health and work of enslaved people, cotton prices, and the purchase of an enslaved boy in addition to the occasional mention of Amherst College. What does it mean for an archives to hold on to such things? Their collection means that the College has long been aware that one of its trustees was an enslaver. These papers and the questions that surround them will be integral to future posts.

While Tyler provides a thorough account of Trask’s life, other Amherst publications have been less forthcoming. Edward Hitchcock’s Reminiscences of Amherst College is one such publication:

With Col. Israel E. Trask, of Springfield, I had not much personal acquaintance. I recolect [sic] him chiefly as a gentleman of fine personal appearance, and we know that he was a liberal subscriber to the fifty thousand dollars fund. What other special efforts he made to promote the object I know not.

As I have been making my way through Mississippi and Louisiana, I have found that while Amherst has so disavowed and intentionally forgotten Trask in recent years, the exact opposite is true of archives and family reminiscences. The Mississippi Department of Archives and History, which houses a 332-folder collection on the Trask-Ventress family, specifically describes Trask as “one of the incorporators of Amherst College.” How did he fade into obscurity at Amherst? Was it a deliberate attempt to forget the institution’s ties with slavery? Or was it something more innocuous?

Regardless of the reason for his obscurity, I hope this and the following posts will bring to the forefront Trask’s relationship to Amherst and Amherst’s relationship to slavery.

*See Carl I. Hammer, “‘Importunity Which Mocked All Denial’: The Amherst Charity Fund and the Foundation of Amherst College,” History of Universities XXX/1-2 (Oxford University Press, 2017), 157-204.

You must be logged in to post a comment.