Perhaps the darkest documented period in Israel Trask’s tenure as an enslaver comes in the form of the 1811 German Coast Uprising.

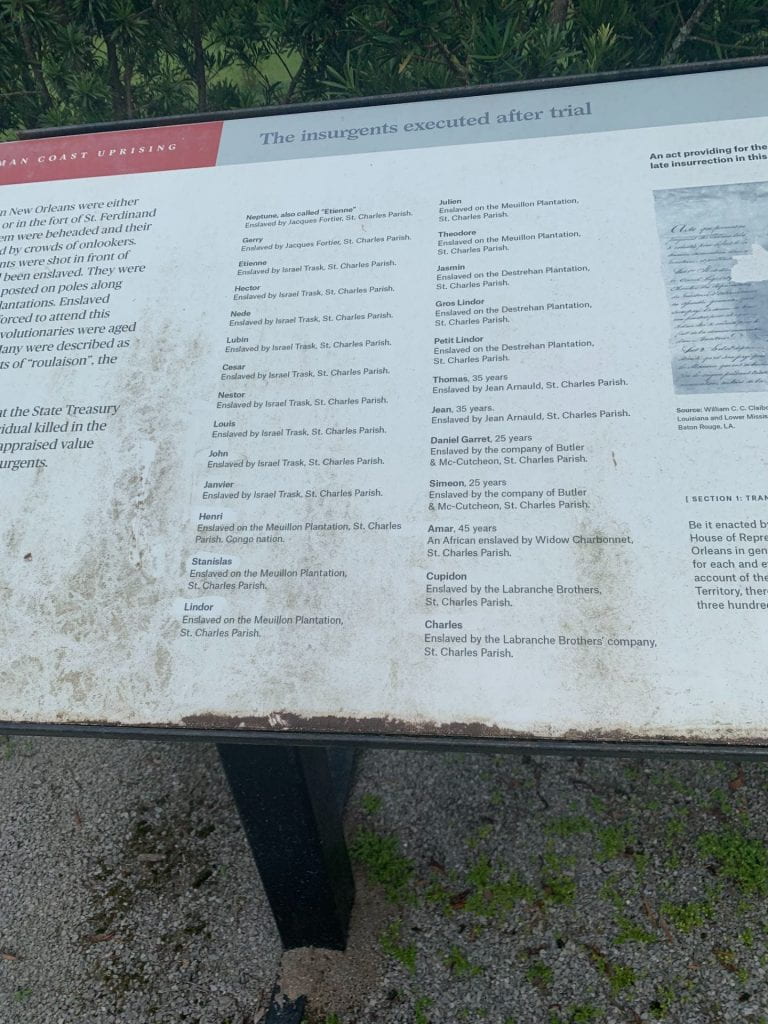

Frequently termed the largest slave revolt in US history, the 1811 uprising spanned two days (January 8-10, 1811), three parishes (St. John the Baptist, St. Charles, and Jefferson), and involved more than 500 participants led by Charles Deslondes, enslaved on the Deslondes plantation. At least 45 were later executed, including nine people enslaved by Israel Trask, and their bodies beheaded and posted on poles along River Road in front of the plantations on which they were enslaved. This recent video by Crash Course Black American History provides an overview of the Uprising.

*****

The previous post in this series focused on Trask’s monetary connections to Amherst College. While this post primarily seeks to highlight the human toll of slavery and of Trask’s part in it, I do want to make one thing clear: slavery was immensely profitable, and profit Trask did indeed. In fact, Trask even profited from the Uprising. As Daniel Rasmussen’s American Uprising: The Untold Story of America’s Largest Slave Revolt (Harper, 2011) lays out,

On April 25, the government decided to act on [Governor] Claiborne’s recommendation—spending federal money to compensate planters whose slaves had died in the insurrection. They passed an ‘Act providing for the payment of slaves killed and executed on account of the late insurrection in this Territory.’ The act provided $300 per slave killed to each planter, and it also provided one-third of the appraised value of any other property destroyed in the insurrection. (118)

At least nine people enslaved by Trask were executed after the Uprising, entitling Trask to $2,700. That is more than three times the amount that Trask contributed to the Charity Fund. #ReclaimAmherst claims that “Black people are the condition of possibility for the existence of Amherst College,” and while this specific amount cannot be directly connected to his contributions to the College, it is part of the process of wealth-building that helped Trask to fund the College.

*****

Whitney Plantation in Wallace, Louisiana, tells the story of the uprising. Etienne, Hector, Nede, Lubin, Cesar, Nestor, Louis, John, and Janvier, all enslaved by Israel Trask, are here recorded as insurgents executed in the aftermath of the uprising. After researching Trask in the safety of my dorm room for a number of months and then journeying to the Mississippi Department of Archives and History where he is chiefly remembered for his association with Amherst College, to see his name displayed so matter-of-factly here was startling. How many other enslavers have a similar relationship to academic and philanthropic efforts? And what can we learn about the people they enslaved?

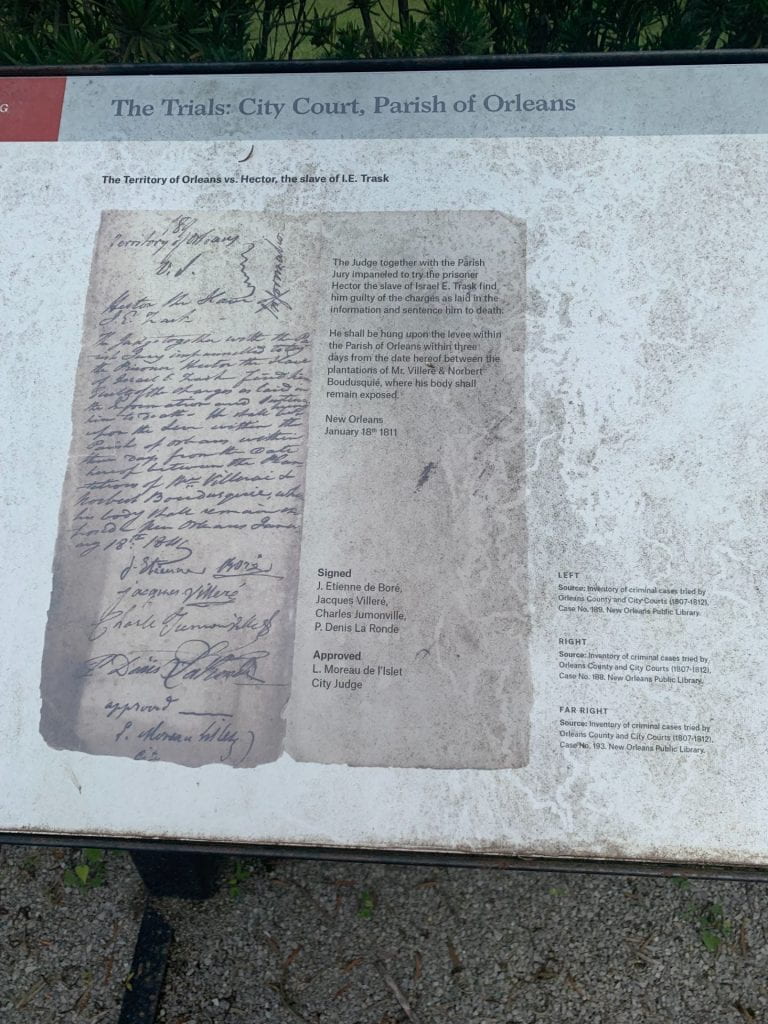

Nicka Sewell-Smith has recovered approximate birthdates and origins for some of the men. The Louisiana Digital Library holds bills of information for Louis, Hector, Cesar, John, and Janvier in either English or French; all were found guilty and sentenced to be hanged.

The first tribunal began at Destrehan Plantation on January 13, composed of Parish Judge Pierre Bauchet Saint Martin and five enslavers. Here, Etienne and Nede were held in a small wash shed (seen below; see the outside of the shed here) with other alleged participants as they awaited trial. While they were held in January in Louisiana, and thus were not likely subjected to extreme heat or cold, to describe the experience of the over twenty men held in this shed while they waited to hear their fate as unpleasant would be a gross understatement. My tour group of about seven people could barely fit in the shed without bumping into anything or anyone. What did Etienne and Nede think about while they were held here? And did they even participate in the Uprising, or were they simply rounded up without cause?

Regardless of their guilt–if one can be guilty of trying to become free–or innocence, Etienne and Nede were tried on the 14th with 11 other men in the back room of the main house. All “confessed and declared that they took a major part in the insurrection which burst upon the scene on the 9th of this month,” according to book 41 of the St. Charles Parish Original Acts, as transcribed by Glenn R. Conrad in The German Coast: Abstracts of the Civil Records of St. Charles and St. John the Baptist Parishes, 1804-1812 (101). However, the amount of coercion at play is unknown.*

After being sentenced to death, the tribunal decreed that “the heads of the executed shall be cut off and placed atop a pole on the spot where all can see the punishment meted out for such crimes, also as a terrible example to all who would disturb the public tranquility in the future” (102). The display stretched for forty miles, intended to prevent such an uprising from happening ever again.

*Conrad attributes Etienne and Nede as belonging to a “Mr. Trax,” but other records suggest that Trax and Trask are the same person.

What is strange, though, is that I was unable to find any evidence of Trask owning a plantation in the area in either the St. John the Baptist or St. Charles Parish Clerk of Court offices, where deeds are held. This could mean one of several things, as suggested by the founder of the 1811 Kid Ory House John McCusker: 1) Trask was a profiteer, falsely claiming that he lost property (enslaved people) in the insurrection in what would now be called insurance fraud, 2) he was sent by President James Madison to disburse those funds, 3) he was an investor in a plantation and sent to deal with the money due to his legal expertise. Indeed, the world of slavery stretched far beyond the sites that are currently preserved as tourist destinations today. By 1858, for example, the entirety of land along the Mississippi River from Natchez to New Orleans was part of a plantation.

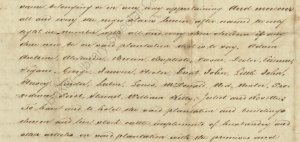

While the third option seems promising as Trask’s name appears nowhere on a map or deed, there may yet be a simpler explanation. In 1810, Trask purchased a plantation “in the Territory of Orleans about fifteen miles outside the City of New Orleans” from Abraham Mann and William Barnard of London for the sum of eighty thousand dollars (a relative inflated worth of $1,823,463.09 today). However, deeds resulting from the sale and others involving the same area were recorded only in Wilkinson County, Mississippi, and in the City of New Orleans.

A copy of the deed held by Baker Library Special Collections in the Harvard Business School lists the names of the enslaved people sold as part of the transaction. Their names are: Adam, Antoine, Alexander, Brown, Baptiste, Cesar, Doctor, Etienne, Figaro, George, Janvier, Hector, Great John, Little John, Hersey, Lindor, Lubin, Louis, McDonald, Ned (possibly Nede?), Nestor, Providence, Perot, Stewart, William, Kitty, Juliet, and Rosette. While many of these were common names for enslaved men, the amount of overlap between this deed and those executed and attributed to Trask suggests that they are one and the same, and that Trask indeed enslaved them.

In 1812, as recounted by William S. Tyler in his History of Amherst College During its First Half Century, 1821-1871, Trask “disposed of his plantations in Mississippi and Louisiana” and returned to his native Brimfield. While it is easy to believe that the two events are linked, that Trask was so disgusted with the institution of slavery after the 1811 Uprising that he never wanted to deal with it again, Trask continued to interest himself with plantations throughout his life either through investments with his brother or through owning a cotton factory in Brimfield. Unfortunately, Trask’s correspondence, as stored in the Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, conveys little about Trask’s feelings on the issue. In his letters, Trask most commonly comes across as almost paternalistic as he infantilizes the enslaved people asking about his wife and children and scarcely talks about them as individuals. However, in one letter addressed to his wife on November 18, 1827, Trask alludes to a punishment meted out to an enslaved man:

Tell Cesar & Lucy their friends are all well an rejoiced to hear that they have not conducted like Spencer. They would be glad to see them. I must remind Cesar to be attentive to the occonomy & cleanliness of the barn. And to keep good fires for you. I trust he will be faithful and Lucy also to all their duties [sic]. (Israel E. Trask Papers, Box 1, Folder 12)

Spencer does not appear in any later correspondence. Cesar and Lucy, of course, would eventually go on to attempt to claim their freedom. But that is a story for another post.

You must be logged in to post a comment.