Although the links between Amherst College and slavery are the initial focus of this project, there are many other issues around race and racism in college history to be addressed.

Missionary Legacy

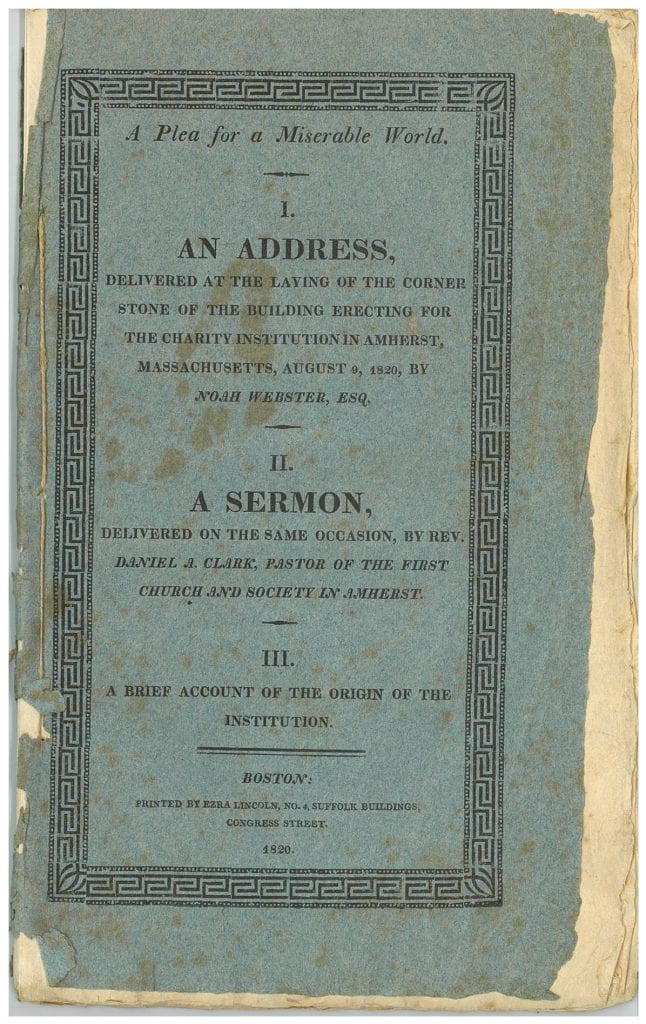

“The object of this institution, that of educating for the gospel ministry young men in indigent circumstances, but of hopeful piety and promising talents, is one of the noblest which can occupy the attention and claim the contributions of the Christian public. It is to second the efforts of the apostles themselves, in extending and establishing the Redeemer’s empire–the empire of truth. It is to aid in the important works of raising the human race from ignorance and debasement; to enlighten their minds; to exalt their character; and to teach them the way to happiness and glory.”

The college was founded to send young men into the world to convert people to Christianity, both within the expanding borders of the United States and abroad. Congregationalist missionaries were famous for establishing schools; Daniel Bliss (AC 1852) was the founding President of the Syrian Protestant College (now American University of Beirut) in 1866 under the authority of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM). Shaw University, the second HBCU in the country was founded in 1865 by Amherst alumnus Henry Martin Tupper (AC 1859) working as an agent of the American Baptist Home Mission Society. Many missionaries also sent cultural property to the college including books, plants and animal specimens, and the Assyrian Reliefs housed at the Mead. There is much to explore in the complex legacy of Amherst missionaries working around the globe.

Scientific Racism

In addition to direct ties to the slave trade, Craig Wilder’s Ebony & Ivy emphasizes the role higher education played in the development and promulgation of scientific racism both before and after the Civil War. Amherst College has a very long legacy of embracing Phrenology, Anthropometry, and Eugenics well into the 20th century. Orson Squire Fowler, Class of 1834, was one of the leading publishers of phrenological literature, as well as works on the water cure and other nineteenth-century health movements. Works published by Amherst faculty and alumni contributed to the rise of scientific racism; the Department of Hygiene and Physical Education Records show how racial science was part of the curriculum.

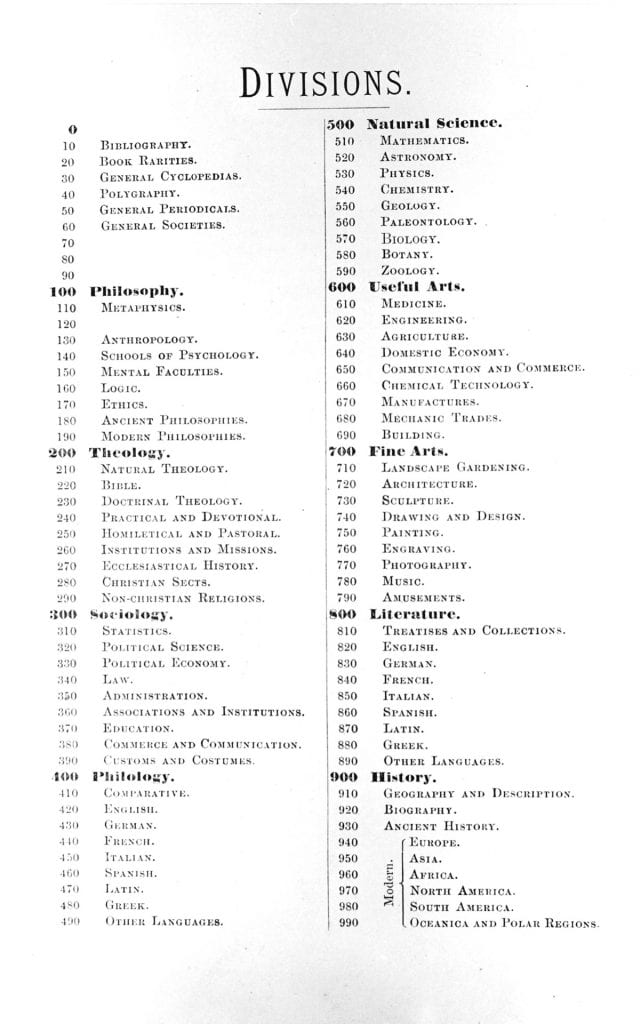

Melvil Dewey, Class of 1874, spent two years after graduation working with faculty to develop a new classification system for reorganizing the college library, then housed in Morgan Hall. Working with the books already in Amherst’s collection, and in close collaboration with Amherst faculty, Dewey developed the Dewey Decimal System, which remains the most widely used classification system for libraries around the world. In Irrepressible Reformer: A Biography of Melvil Dewey, Wayne Wiegand describes the product of that work:

“As a result, the hierarchical arrangement Dewey cemented into the DDC had the effect of framing and solidifying a worldview and knowledge structure taught on the Amherst College campus between 1870 and 1875. By the end of November [1875], Dewey had completed his scheme and was ready to have it printed. (29)

Jonathan Furner’s article “Dewey Deracialized: A Critical Race-Theoretic Perspective” (Knowledge Organization, volume 34 (2007), issue 3) neatly summarizes the current critique of the Dewey Decimal System. In 2019 the American Library Association issued a statement regarding their decision to remove Dewey’s name from a prominent award.

Japanese American Internment

John J. McCloy, Class of 1916 and Trustee of Amherst College from 1947 – 1969 was the chief architect of Japanese-American Internment during World War II. The John J. McCloy Papers is one of the most heavily used collections in the Archives & Special Collections and his role in both implementing Internment in 1942 and his lifelong opposition to reparations or a formal apology are very widely known. This review of the biography The Chairman, John J. McCloy: The Making of the American Establishment by Kai Bird summarizes McCloy’s views:

“In McCloy’s case, as Bird points out, an obsession with communism and national security led to extreme behavior of a different sort. McCloy was so obsessed with the possibility that communist saboteurs might slow the production of essential goods in World War II that he wanted illegal wiretaps used to break labor strikes. “We have to restrain our liberties to preserve them,” he explained in Orwellian doublespeak (p. 136). Fear of sabotage also inspired McCloy’s support for the wartime internment of Japanese-Americans, even though the program amounted in his own mind to a flagrant violation of the Constitution. The Constitution was, in his words, “just a scrap of paper” when it got in the way of national security as the War Department defined it (p. 147). McCloy pursued the internment program despite opposition from the Justice Department and long after U.S. victories in the Pacific made the program blatantly unnecessary. At that point, he defended the internment in order to protect the reputation of men like himself, who had instituted the program in the first place. He worked overtime to prevent legal challenges and even went so far as to draft legislation that would suspend the writ of habeas corpus for Japanese-Americans. Slight wonder that Harold Ickes thought McCloy “inclined to be a Fascist” (p. 161).” (Hogan, Michael J. “The Vice Men of Foreign Policy.” Reviews in American History, vol. 21, no. 2, 1993, pp. 320–328. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2703220)

“Lord Jeff” and Colonialism

The Archives holds a wealth of information about the historical figure of Lord Jeffery Amherst and the Amherst mascot “Lord Jeff” including a substantial collection of manuscripts, some already online. Archives also holds materials documenting his nephew William Pitt Amherst’s diplomatic missions to China and India in the early 19th century. Beyond the Amherst family, Archives holds a collection of manuscripts — The Plimpton Collection of French and Indian War Items, 1670-1934 — that documents the violence of colonialism in New England. Additional local resources on the history of the area during the colonial era are available through the Jones Library, and the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. New England is home to an abundance of historical societies, museums, archives, and libraries that document the colonial history of the region.

You must be logged in to post a comment.