As someone who is not particularly athletic, I have never had much cause to venture to Pratt Field. When was it built, and why is it named after him–and which Pratt is he? I have never completely understood why Amherst College has so many things named after Pratts–Pratt Field, Charles Pratt (gymnasium, natural history museum, and now dormitory), and Morris Pratt dormitory–when there are other, less confusing options. In the case of Pratt Field, there is a much longer–and nonathletic–history that sheds light on Amherst’s racial legacy and relationship to philanthropy.

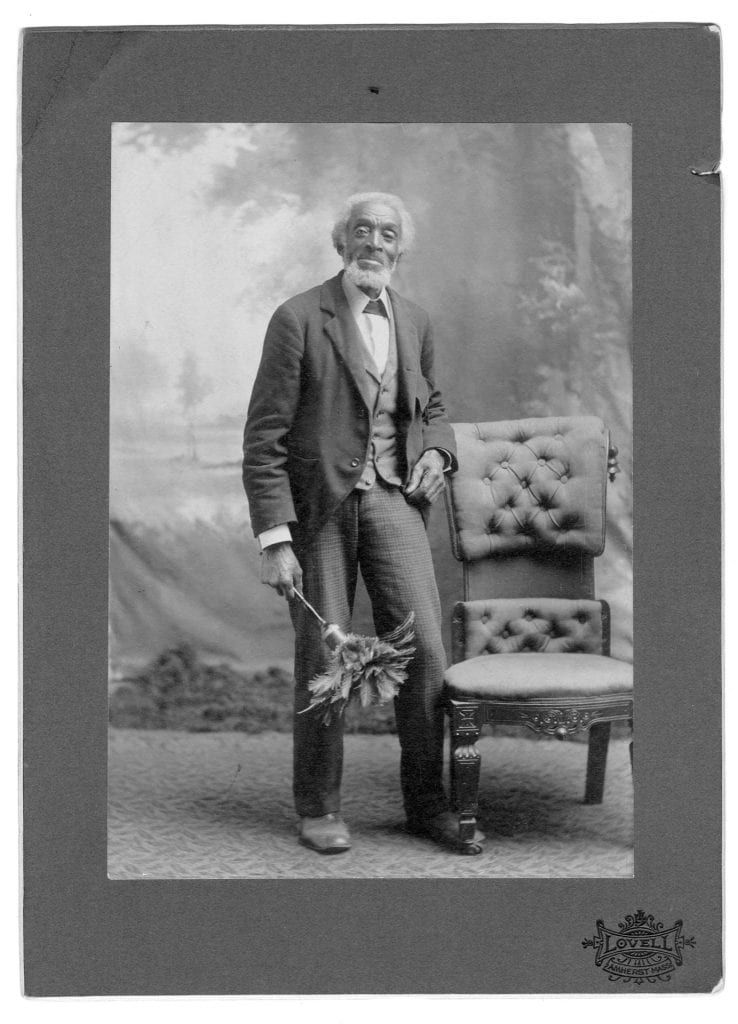

My name is Anna Smith and I am a junior American Studies major and student assistant in the Archives working with the Racial History of Amherst project. While this project seeks to uncover people associated with the College with direct ties to slavery such as Israel Trask, it also seeks to highlight the previously hidden voices of BIPOC associated with the College. This involves moving beyond alumni; though Edward Jones (AC 1826) was the only Black student on campus during the 1820s and the only Black graduate for several decades, he was not the only Black man to join the Amherst College community in the first half of the nineteenth century. There was also Sambo Coon/Kuhn,* a formerly enslaved man who worked at the College from 1828 to 1854, and Charles “Prof. Charley” Thompson, a former servant of President William Augustus Stearns who began working at the College about 1856.

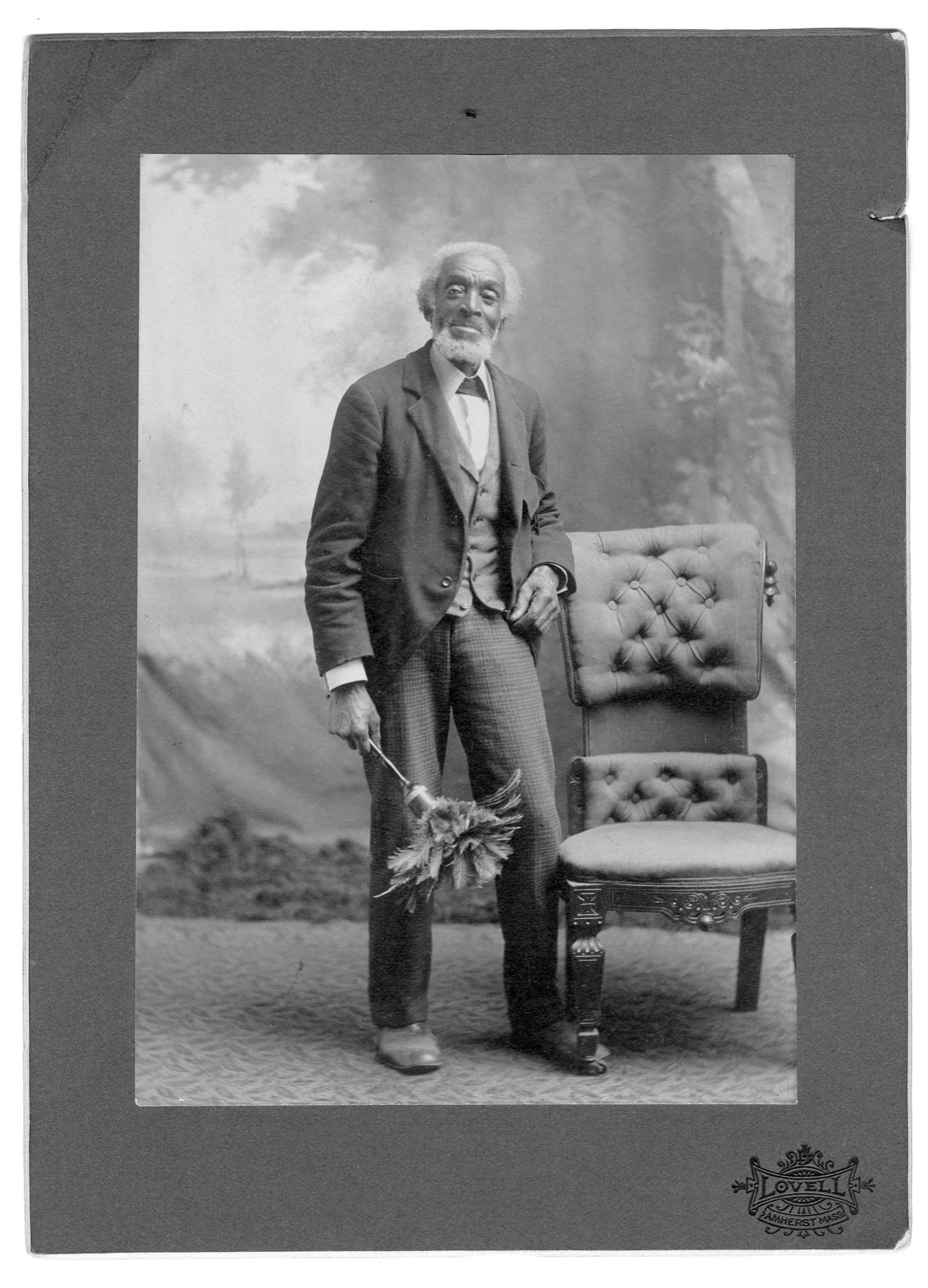

Unlike the Pratts, neither of these men are visibly memorialized on campus; few even know of their existence. Mimi Dakin has tracked Thompson’s voyages at sea, but I was curious about Thompson’s on-campus legacy–have we occupied the same spaces? In her post, Mimi links to “Prof. Charley”: A Sketch of Charles Thompson, written in 1902 to raise money for Thompson’s old age by President William Augustus Stearns’ daughter Abigail Eloise Lee. Lee writes:

Many of the older graduates can recall him as he looked some twenty or thirty years ago, coming from the old College well, with his two pails of water, a welcome visitant to the then comfortless rooms of North and South College.

So many years he has toiled up and down the College hill, shovelled the walks, “tended the b’iler,” swept the halls and made the fires, that he has come to feel himself a part of the machinery of the College, and with some claim, in his declining years, on his Alma Mater. (5-6)

In the context of debates on other college campuses about the naming of buildings, I was particularly struck by Lee’s account that

soon after his marriage [in the late 1850s], the College built for him the little house that stands at the foot of the president’s orchard. And here, as sub-janitor of the College, Charley lived close beside his best friend and benefactor [President William A. Stearns]. (16-17)

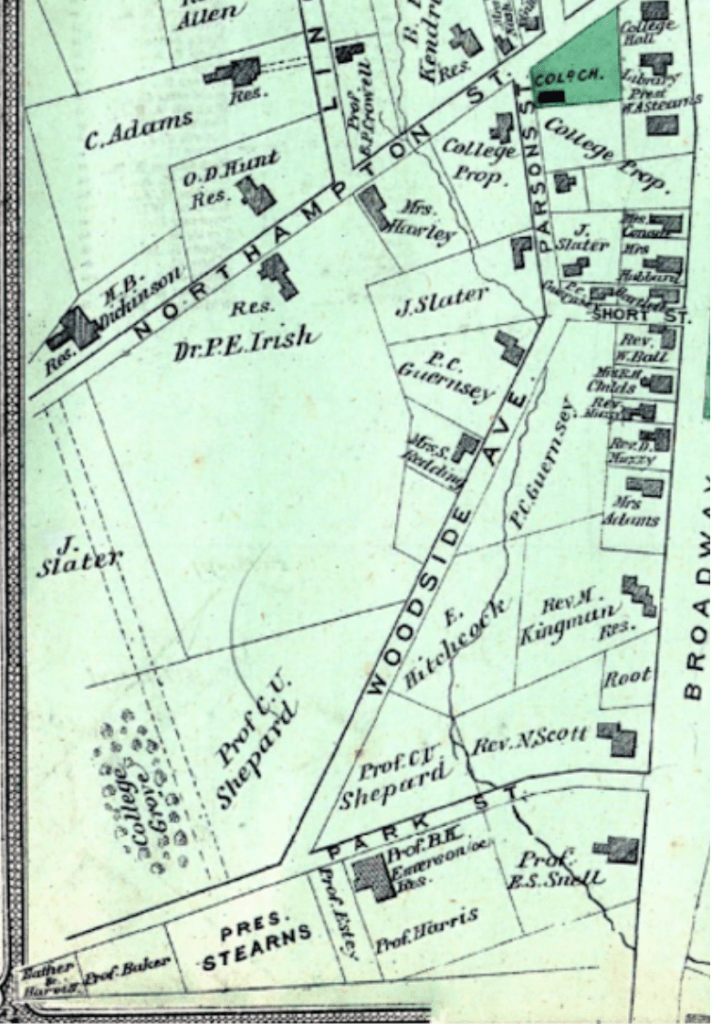

Where is this house? A part of me hoped that it was a shed in Biddy’s backyard, if only so that I knew it still existed and was owned by the College. While I have not been able to find any map referring to a “president’s orchard,” the land in the 1873 map shown below fits the description–a piece of undeveloped land next to President Stearns.

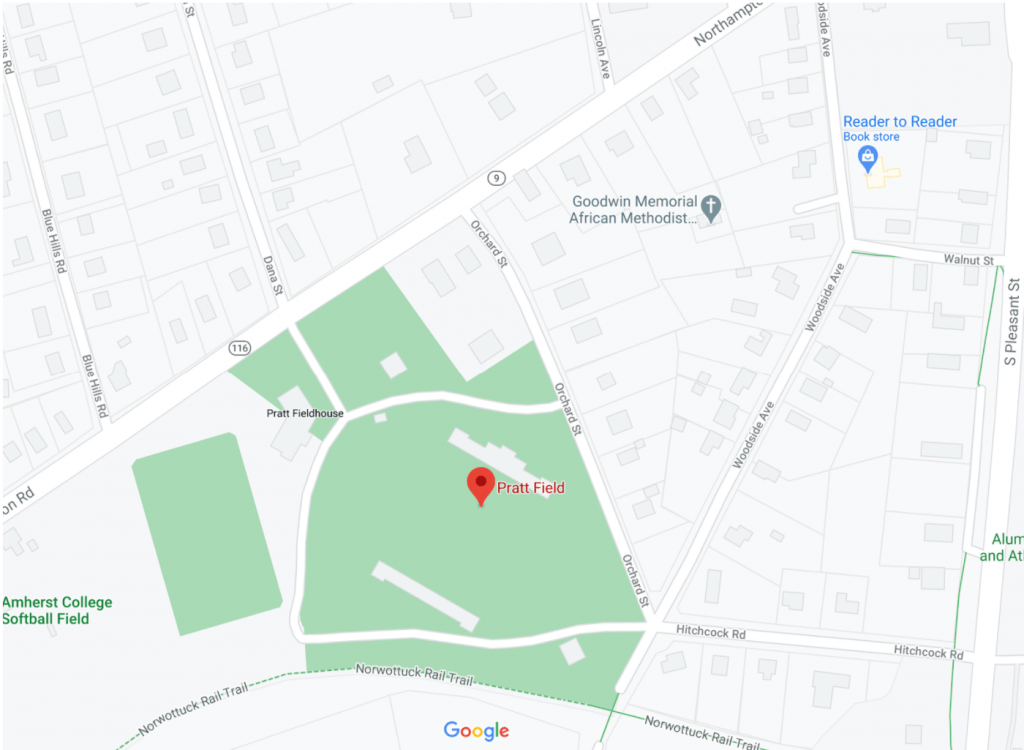

Google Maps puts it in greater context:

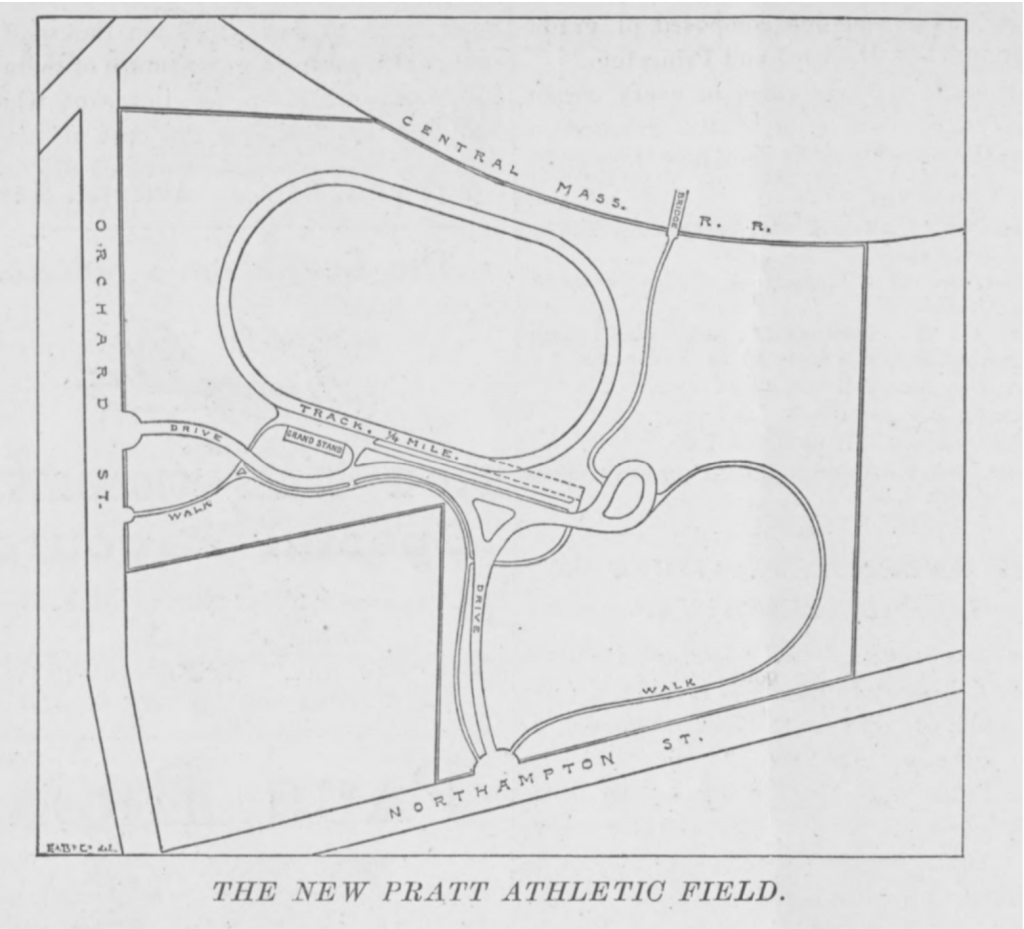

It’s Pratt Field! So why is it named after Frederic Pratt (AC 1887), rather than a man who served the College for over forty years? The answer is money–the September 28, 1889, issue of The Amherst Student reports that “our well known Gym. Captain of ‘87 has purchased the original athletic grounds, which were condemned for the Mass. Central R.R., of about three acres, and another adjoining five acres.” Charles Pratt (AC 1879), Frederic’s brother, funded the construction of Charles Pratt and Morris Pratt dormitories, the latter of which is named for his son.

This naming of buildings and grounds after donors is a common and ongoing practice at the College. The former fraternity houses pose a notable exception, however, as they were renamed in 1984 for those “who in a variety of ways had performed distinguished and distinctive service to Amherst.” Drew House, formerly Phi Alpha Psi, is the only building named after a Black alumnus.

In May 1891, members of the College, including Dr. Edward Hitchcock and President Merrill Gates, dedicated the Field. A pamphlet published after the event extolled the virtues of the new space:

The Pratt Field is five minutes’ walk from the College Campus. It contains thirteen acres graded with all accuracy, and prepared for use as running-track and base-ball grounds, and for tennis, golf, lacrosse, and other out-door games. … Adjoining the Pratt Field is a grove of original pines, six acres in extent; and still beyond, the old ball field of four acres additional. From The New Pratt Field at Amherst: The Finest College Athletic Field in the Country, Amherst Athletism [sic], in Chi Psi scrapbook.

While the chief goal of the field was to provide a space for athletic activities, it was also intended to be a place of beauty. In pre-pandemic times, members of the public enjoyed full access to the Field.

It is unclear if any homes were razed to make way for the field. Property records indicate that currently-standing surrounding houses primarily date from either 1875 or 1900. In any case, by 1886, Thompson had moved out of the original property into a house on nearby Baker Street, safely outside the Pratt Field construction.

Baker Street, in addition to Snell Street, Northampton Road, and Hazel Avenue, are part of the Westside Historic District. Added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2000, Westside is a historically Black neighborhood just beyond Pratt Field. Just like Thompson, there appears to be little public recognition of the space.

Earlier this week, I finally walked over to Pratt Field. The field itself is entirely modern, gated off from the surrounding turn-of-the-century houses; no trace of Thompson remains on this College-owned property. While I was not able to walk to Thompson’s house due to quarantine restrictions, I was able to partially recreate his long walk up the hill to South College. When walking around campus, it is important to remember that more people have operated in the same spaces than the names on the buildings would suggest. Each of these people have their own stories to tell.

*Despite the racist origins of the name, census, payroll, and death records indicate that Kuhn/Coon used either variant of this name throughout his life.

You must be logged in to post a comment.