Slavery in New England

Slavery was widespread across New England in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries but that history is often lost, obscured by the rise of abolitionist sentiment and activism in the region. The decline of slavery and the rise of abolitionism in New England were not the results of anti-racist actions or beliefs. Marc Howard Ross in Slavery in the North: Forgetting History and Recovering Memory writes:

“With the onset of the American Revolution, challenges to Northern slavery and calls for abolition increased. Northern abolition, however, was generally very gradual, and the rates at which it occurred varied widely across the states. In no way, however, were abolitionists in favor of equality.

For whatever combination of reasons, by the early nineteenth century, the majority of Blacks in the North were no longer enslaved. Nor did they have equal rights as citizens. Generally, they were treated as outcasts living in segregated worlds, with limited job opportunities, and they were targets of severe discrimination.” [Marc Howard Ross. Slavery in the North: Forgetting History and Recovering Memory. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018. Pages 56-57.]

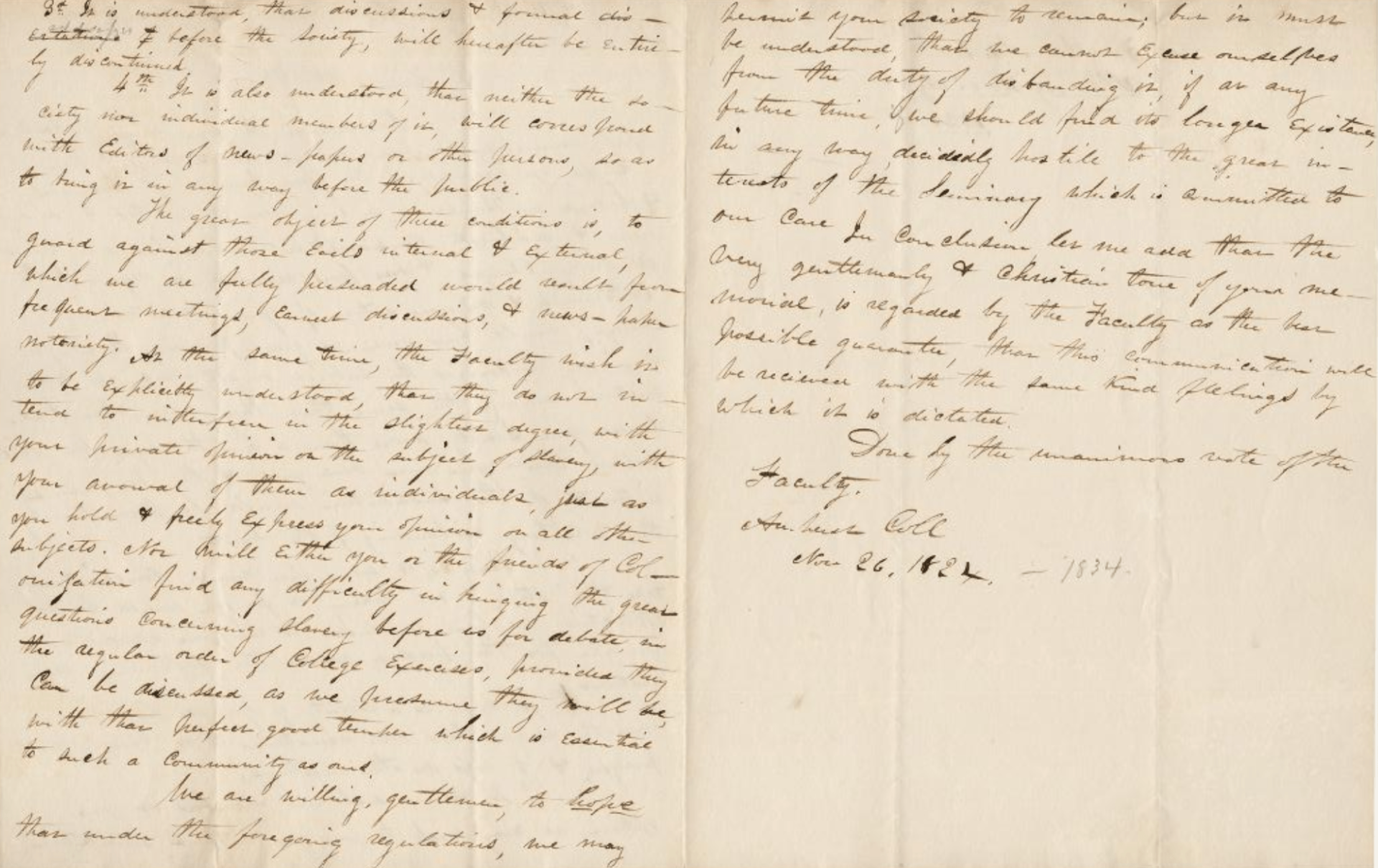

The “forgetting history” of Ross’s subtitle is on display in The History of the Town of Amherst, Massachusetts published in 1896. In a section dedicated to “Slavery and the Abolition Movement,” nearly 150 years of slavery in Massachusetts is described in two sentences: “Slaves were owned in Amherst as late as 1770. There was little active opposition to the institution of slavery in this section until after 1830, although few persons were held in bondage in Western Massachusetts after the beginning of the Nineteenth Century.” (p. 464) The 1830s anti-slavery activism by the students of Amherst College is explored in Michael E. Jirik’s essay ““We are and will be forever Anti-Slavery Men!” Student Abolitionists and Subversive Politics at Amherst College, 1833–1841” in the Bicentennial volume Amherst in the World. There is much more to explore as chattel slavery in Massachusetts was sometimes replaced by other forms of bondage such as indentured servitude.

Please see Readings and Resources for additional reading suggestions and web links.

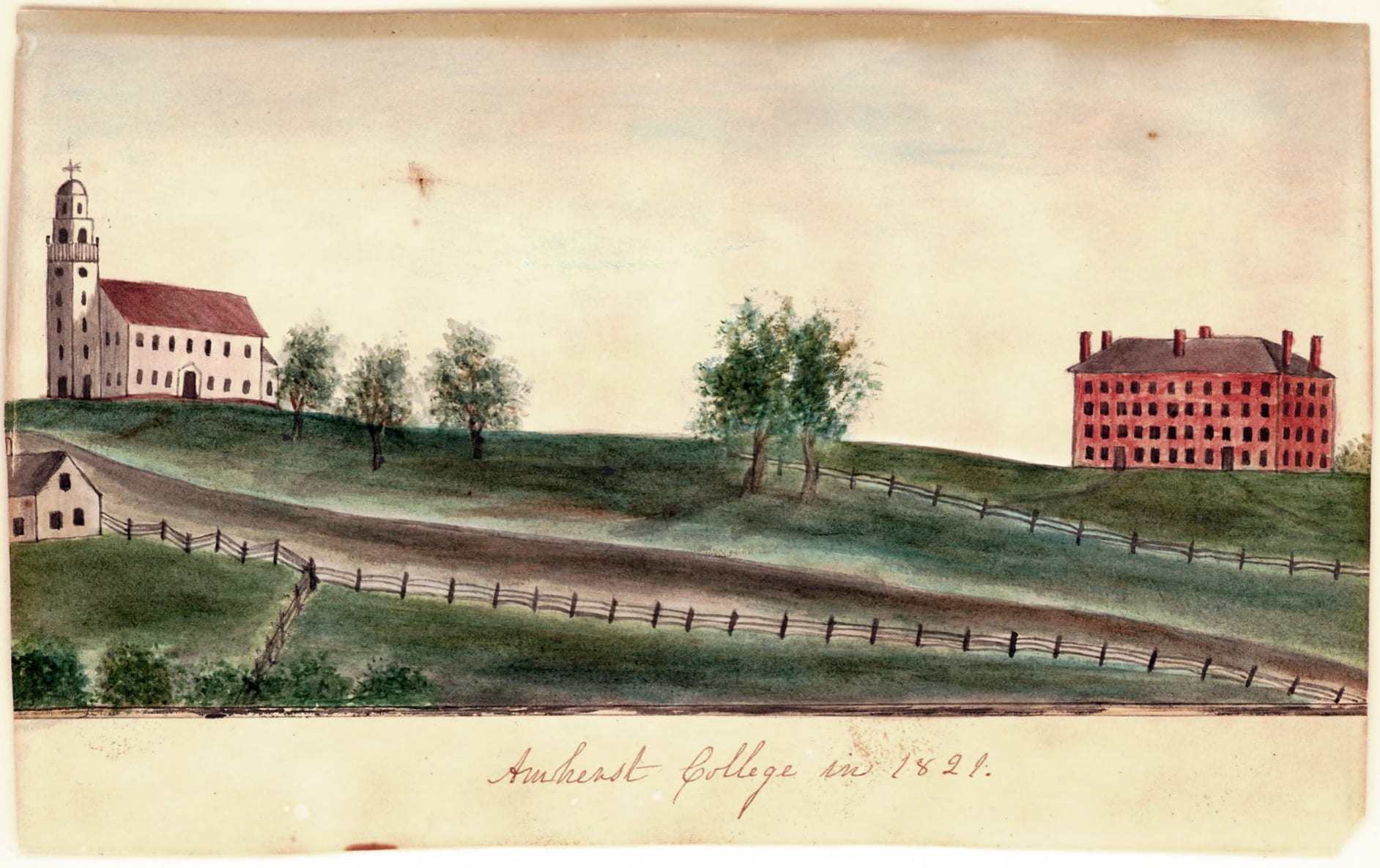

Slavery and Amherst College

There are three people associated with Amherst College with direct ties to slavery. New information will be added to this page as research progresses.

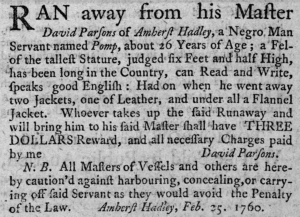

Rev. David Parsons (1712-1781)

Rev. David Parsons (1712-1781) was the Minister at the First Church of Amherst and held three people in slavery: Pompey, his wife, Rose, and their son, Goffy. The church itself was located approximately on the site now occupied by The Octagon; that land was given by the town to the college in 1840. Parsons’s son, also named Rev. David Parsons (1749-1823), was a founder of Amherst Academy; he was a supporter of the Charity Fund and the college. It is unclear what happened to Pompey and his family; were they freed at Parsons’s death in 1781? Did they remain in the area? Can we trace their descendants? How widespread was slavery in and around the town of Amherst?

Information on Rev. David Parsons, Pompey, Rose, and Goffy is included in at least two books: The History of the Black Population of Amherst, Massachusetts, 1728-1870 by James Avery Smith (New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1999) and Slavery in the Connecticut Valley of Massachusetts by Robert H. R0mer (Levellers Press, 2009). As more information comes to light, we will share it in this space and elsewhere. Details of the establishment of Rev. Parsons as minister in Amherst are available in The History of the Town of Amherst, Massachusetts (1896) Chapter V.

Col. Israel E. Trask (1773-1835)

Col. Israel E. Trask (1773-1835) was a donor and an Amherst Trustee from 1821 until his death in 1835. Trask was born in Massachusetts and moved to Mississippi in 1801. He briefly established a law practice in New Orleans, was involved in the handover of the Louisiana Purchase, and ran a cotton plantation in Woodville, Mississippi in partnership with his brother, James L. Trask. Israel Trask moved back to Massachusetts in 1812 where he acquired a textile mill, but he spent many months each year in Mississippi and continued managing his plantation until his death in 1835. The Archives holds a small collection of Trask’s manuscript correspondence which includes frequent references to enslaved people and his plantations and few mentions of Amherst College; more material is available at Harvard University. The Archives holds one letter from founder Rufus Graves to Trask and four letters from President Heman Humphrey to Trask; no letters from Trask to anyone at Amherst have been found yet; most of the letters from Trask are to his wife. He was not a major financial donor to the college but his political connections in Boston during the Charter fight made him an important member of the Trustees. He also seems to have shared a strong interest in missionary work and “Oriental languages” with the founders. The total value of his cash gifts appears to be $710. Much more research is required.

By a remarkable coincidence, professional genealogist Nicka Smith has spent nearly a decade tracing her ancestry to the people enslaved by Israel Trask and his family. She gave a presentation on her research at Amherst in October 2021: “Held in the Balance: The Trask 250”

Anna Smith (AC 2022) has written a series of posts about Trask for the Racial History Blog. Full digitization of the Trask manuscripts for addition to Amherst College Digital Collections will take some time; fortunately the collection includes a typed transcription of all of the documents which is available as a PDF download. Anna Smith also took digital photos of the entire collection to support her own research, which are also available for download as a series of PDF files:

- Transcription of the Israel E. Trask Papers in the Amherst College Archives & Special Collections:

- Research images of the Israel E. Trask Papers in the Amherst College Archives & Special Collections:

Oliver Cowls

New information about Oliver Cowls was provided by researchers working on the Reparations for Amherst timeline. Cowls’s son Rufus Cowls was a founder of Amherst College : “Circa 1790 – Wealthy Wheeler, a five-year-old girl who was born in the southern United States, was purchased by Oliver Cowls, farmer in North Amherst. According to census records, Wealthy Wheeler remained in the household of Oliver’s son Levi through 1870, when she was eighty-five years old. The purchase of Wealthy is the last mention of slavery in the historical records of Amherst. Oliver’s son Dr. Rufus Cowls became a moderator at town meeting, a selectman, and a founder of Amherst College. Oliver’s brother Jonathan was a farmer in North Amherst whose descendants operate businesses under the Cowls name in Amherst today.”

The land that Rufus Cowls pledged in support of the college was identified as lying in Houghton Plantation in Washington County, Maine and valued at $3,000 according to the Charity Fund ledger. This deed transferred ownership of the land to the Trustees of Amherst Academy on October 6, 1824. The deed does not record how Rufus Cowls came into possession of this land, but it is an example of the ongoing dispossession of the Indigenous inhabitants of New England. Washington County, Maine is located in the traditional homelands of the Passamaquoddy. Washington County, ME is currently home to the Passamaquoddy Pleasant Point Reservation and the Passamaquoddy Indian Township Reservation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.