What do an academic prize, slavery, and cereal have in common? The Kellogg family.

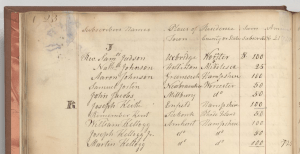

While transcribing the Charity Fund register and records book, 1818-1840, I noticed a name with which I was vaguely familiar.

William, Joseph Jr., and Martin Kellogg of Amherst donated a combined total of 250 dollars (or about $5,370 today) to the Charity Fund. Due to some background reading on the history of slavery in Amherst, I also knew of Ebenezer, Daniel, and Ephraim Kellogg, who Robert Romer had identified as slave owners in his Slavery in the Connecticut Valley of Massachusetts (Levellers Press, 2009):

Dr. Richard Crouch of Hadley reported his medical treatments of the slaves of several owners who lived in East Hadley.

1731-1746 Ebenezer Kellogg Negro Child

1735 Richard Chauncey [?] for wife, your boy & negro.

Blisters & bleeding & med.

1736-1742 John Ingram Tully your negro

1751-1756 Daniel Kellogg For wife, negro, self, child …

1755 Ebenezer Kellogg Negro kicked with a horse ca.

1758 Ephraim Kellogg [?] for his negro (183)

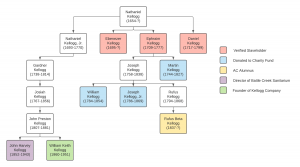

As a result, I began wondering how the Kelloggs in the Charity Fund were connected to the Kelloggs in Dr. Crouch’s register. Were they related? If so, did William, Joseph Jr., and Martin inherit the enslaved people mentioned above? And what does this have to do with the Kellogg Prizes (“established by Rufus B. Kellogg of the Class of 1858, [the awards] consist of two prizes that are awarded to members of the sophomore or freshman classes for excellence in declamation”)? After spending some time on Ancestry.com, I finally had some answers.

Ephraim Kellogg is the grandfather of William and Joseph Jr. and the father of Martin Kellogg. William and Joseph Jr.’s nephew is Rufus Beta Kellogg, the Amherst College alumnus and trustee. Ephraim, along with brothers Ebenezer and Daniel, were slaveholders. According to Sylvester Judd’s 1905 History of Hadley, Ebenezer enslaved multiple people, Ephraim “had a slave,” and Daniel “had… a negro, probably a slave.” I have yet to recover the names of the enslaved.

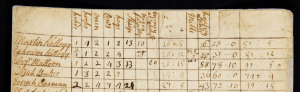

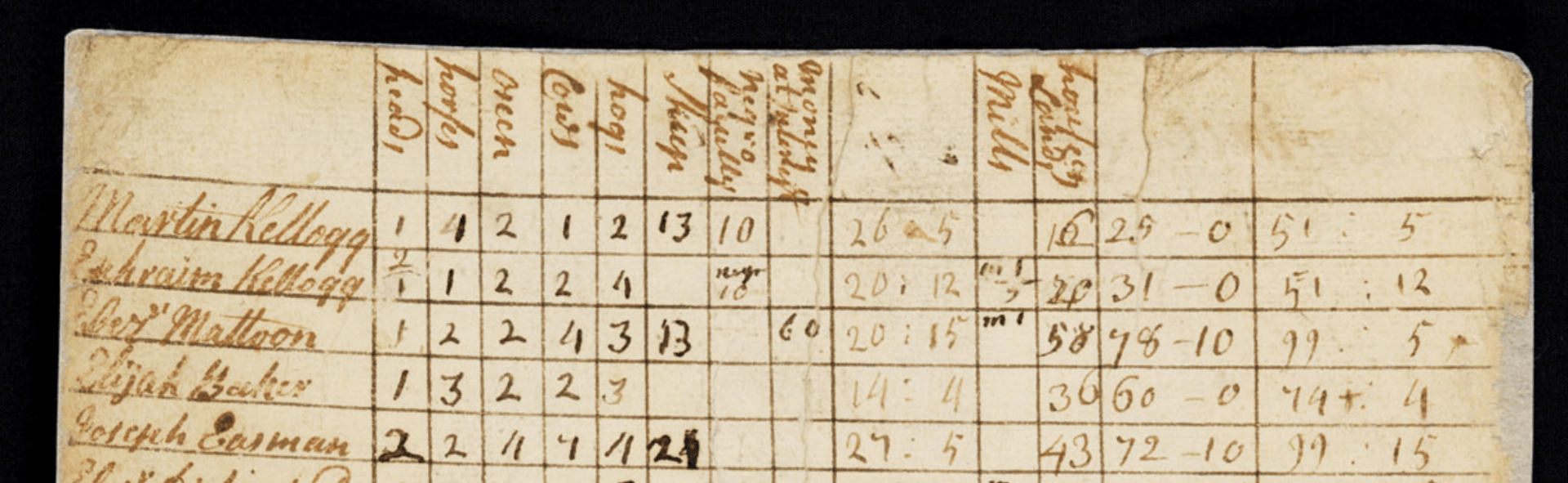

I also still don’t know when this line of slaveholders ended. Slavery was effectively abolished in Massachusetts in 1783, ruling out William and Joseph Jr. (though they surely profited from their family’s legacy). Martin, though, is from a previous generation. The 1770 Town of Amherst tax records indicate that he and Ephraim were taxed for “negro faculty.”

However, the 1771 Massachusetts Tax Inventory lists only two owners of “servants for life,” neither of which are Kelloggs (they are John Adams and Josiah Chauncey). Notably, there is a “Doc’r Kellogg” of Hadley listed as an owner; his relationship to the Amherst Kelloggs remains unclear. Due to my unfamiliarity with colonial Massachusetts tax law, I am not entirely sure of the difference between “servants for life” and “negro faculty.” The “Act for Enquiring into the Rateable Estates of this Province” defines “servants for life” as “all Indian, negro or molatto [sic] servants for life, from fourteen to forty-five years of age,” but there does not appear to be a common definition of “negro faculty.” Even still, it is clear that Martin and Ephraim profited from Black labor.

Unlike Israel Trask, the Kellogg name continues to live on at Amherst; the Kellogg Prizes are still given out today. In town, Kellogg Avenue connects North Pleasant and Triangle streets. It is unclear which Kellogg the avenue is named for, but just as Rufus Beta Kellogg did not directly profit from slavery, his family did. This profit allowed them, in part, to contribute to the Charity Fund and send Rufus to the school they helped to establish. Slavery was not simply about the relationship between the enslaver and the enslaved, but also about the various people and institutions that helped to ensure (and profit from) that relationship. In uncovering and understanding these connections, one can better understand Amherst College’s racial legacy.

P.S. I promised earlier that there was a connection to cereal. William Keith (W.K.) Kellogg, third cousin once removed of Rufus Beta Kellogg, was the founder of the Kellogg Company and co-inventor of corn flakes along with his brother. If you have ever gotten cereal from Val (or any grocery store), you have probably had Kellogg’s.

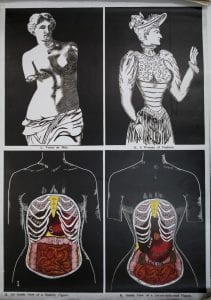

In a strange turn, though, Amherst College Archives and Special Collections actually has posters created by John Harvey Kellogg. Preservation Specialist Mariah Leavitt writes in a blog post that

“Best known as a co-inventor of corn flakes (with his brother), he also ran a sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan with a focus on healthy eating, exercise and enemas. He published extensively and advocated for many causes, from the very reasonable to the merely quirky to the downright terrible. He was a champion of vegetarianism, an anti-smoking advocate, and was clearly opposed to corsets. However, he also promoted almost complete abstinence, was so opposed to masturbation that he recommended genital mutilation to prevent it, and was a significant player in the American eugenics movement.”

Amherst, too, was a player in the eugenics movement, especially with regard to anthropometry. So, lest you think that Amherst College’s connection to Kellogg’s cereal and corsets is simply some weird connection and a fun trivia question, remember that there is always more than meets the eye.

You must be logged in to post a comment.