I am now several months from graduating and completing the senior thesis that originated in a series of blog posts on this site regarding Israel Trask, his relationship to Amherst College, and his life as an enslaver. While I am proud of the work I have done, something has been nagging at me, something that I was unable to explore in the 164 pages of my work that I ultimately left as a single footnote:

There is an interesting connection between Trask and one of Amherst’s most famous families, the Dickinsons. Emily Norcross Dickinson, mother of poet Emily Dickinson, was herself the daughter of a man involved in the founding of Monson Academy. Her husband, Edward Dickinson, and son, William Austin Dickinson, would serve as treasurers of the College. More work must be done to understand the ties between the two families.

This is the time to do that work.

Understanding Emily Dickinson

The Lamp burns sure – within –

Tho’ Serfs – supply the Oil –

It matters not the busy Wick –

At her phosporic toil! Phosphoric

The Slave – forgets – to fill –

The Lamp – burns golden – on –

Unconscious that the oil is out –

As that the Slave – is gone.*

This short poem, written about 1860-1861, marks the single time Emily Dickinson used the word “slave” in all of her extant poetry. Like many, these words have troubled and captivated me for some time; was Dickinson writing in a liberatory sense, referencing the impending Civil War and showing her support of enslaved people who claimed their freedom? Or was she simply writing about the hidden labor of women? Dickinson certainly knew formerly enslaved people–one of the most well-documented workers in the Evergreens (Emily’s brother Austin and her sister-in-law Susan (Sue)’s household, neighboring Emily’s own) is “Aunt Abbie.” Abbie Shaw became a nursemaid for Austin and Sue’s first child, Ned, in 1861 after having been referred to Sue from the Bowles family. Born about 1800, Shaw had been enslaved in Georgia before being unofficially manumitted and traveling to Springfield. The Dickinson households employed a number of other Black workers, and the family may have even crossed paths with people still enslaved, like those that Israel Trask’s widow continued to bring to Massachusetts after his death.

Still, given Emily Dickinson’s relative silence on political issues, I am disinclined to believe that Emily was referencing race and enslavement, especially given the combined use of “serfs,” a term largely relegated to discussion of medieval Europe, and “slave.” Dickinson lived around Black people, but she did not live with those her family employed, and they rarely show up in her correspondence beyond mention of their paid duties.

Recently, I have been working as a podcast researcher for The Slave is Gone, the show that talks back to AppleTV+’s Dickinson. There is a particular scene in the first season where Emily, her sister Lavinia, and their friends are discussing the impending Civil War. “It would be economically devastating for everyone,” one character says, wearing a white cotton nightgown reminiscent of the white cotton wrapper that Emily Dickinson is so famous for wearing. Tasked with investigating these ties in the context of the Dickinson family, I have been thinking about this poem in a new light. What if we focus not on the “Slave,” but on the “Oil,” moving our understanding of the work from a personal-political one to an economic one? The image of a lamp that burns long after it is lit recalls readily the idea of generational wealth.

The Cotton Connection

As I have written previously, Edward Dickinson, Emily Dickinson’s father and treasurer of Amherst College, received a payment on behalf of the College of three hundred dollars upon Israel Trask’s death in 1835. But the connections between the Trasks and the Dickinsons run much deeper than a postmortem donation to an institution of higher education. Instead, the two families are representative of the complicated web of financial and personal relationships between the North and South in the antebellum, one that makes the former directly implicit in the economy of enslavement.

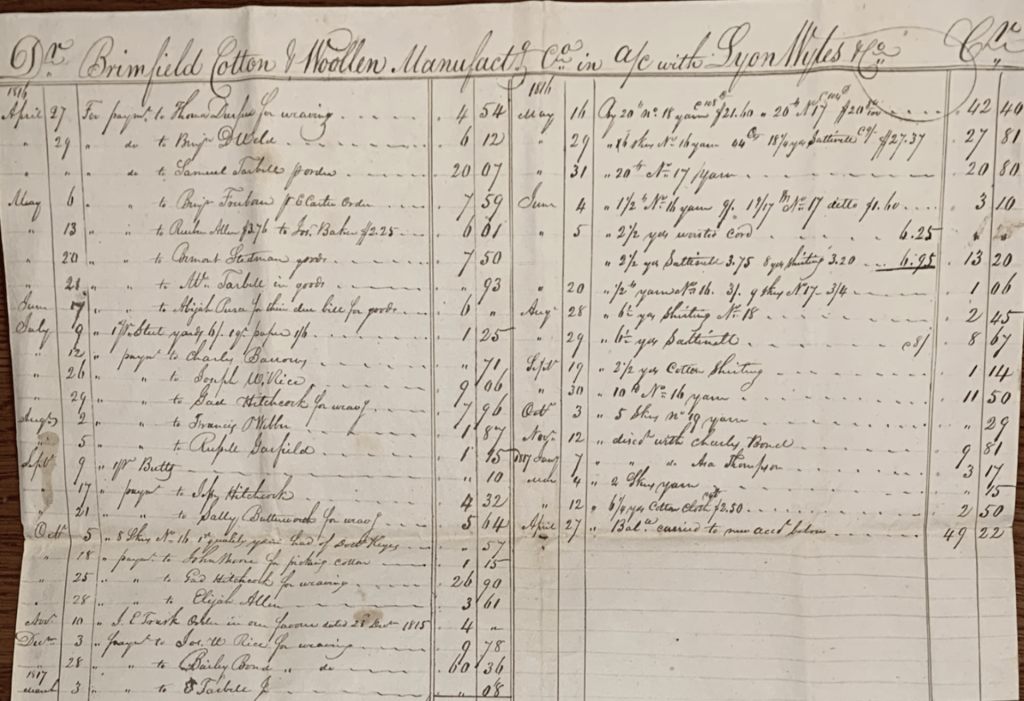

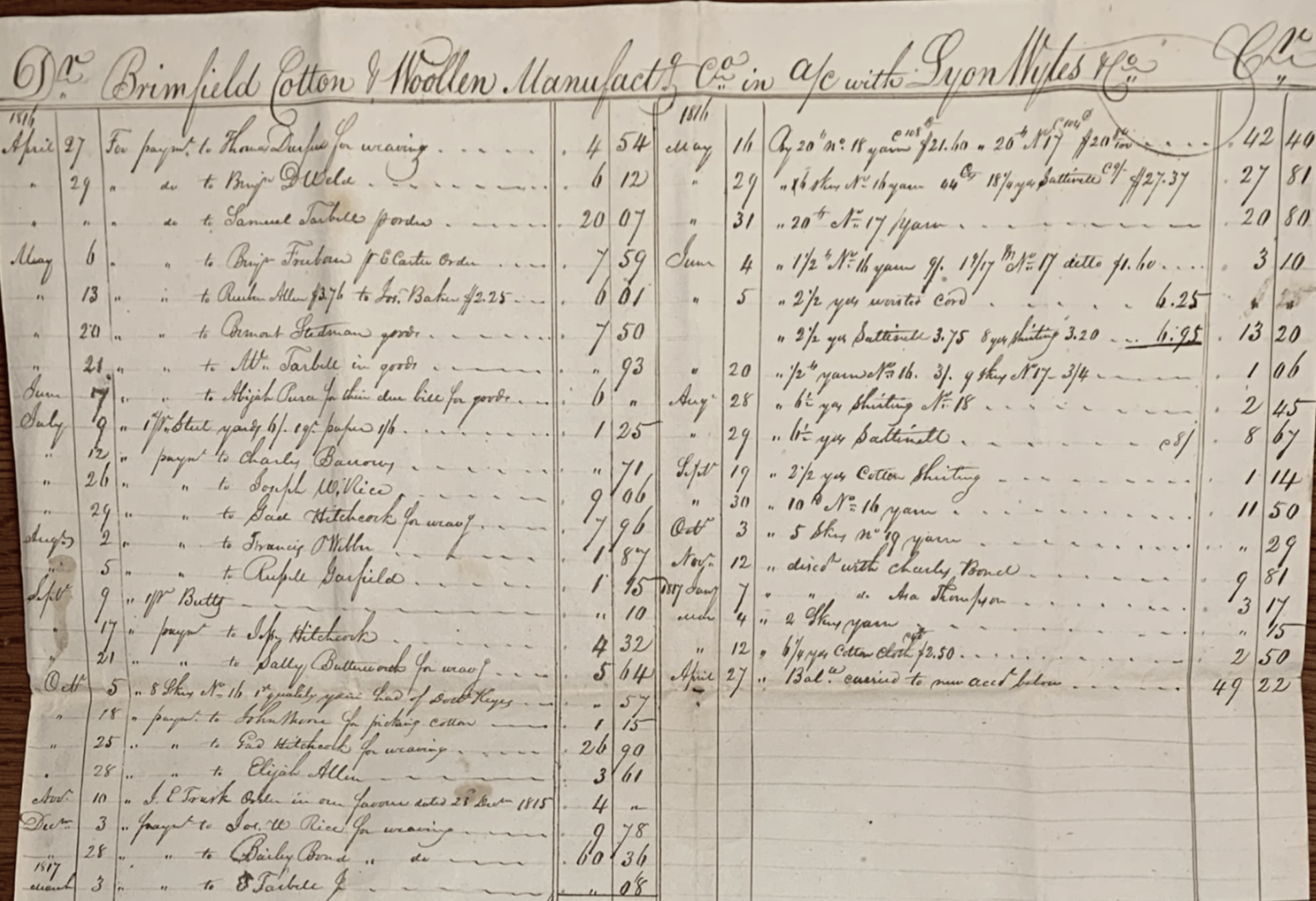

After divesting from the everyday duties of plantation life in 1812 by ceding his plantations to his brother, Trask returned to Brimfield. In 1815, in combination with Elias Carter, Elijah Abbot, and Augustus and Edwin A. Janes, Trask established the Brimfield Cotton and Woolen Manufacturing Company. Though most of the factory’s records are unaccounted for, Harvard Business School’s Baker Library holds a record of the factory’s account with Lyon, Wyles, and Co. dated between 1816 and 1818.** The same year the account was established, the factory was mortgaged to Wyles, Lyon, and Norcross, who soon merged the establishment with their Union Cotton Factory Company to create the Monson and Brimfield Manufacturing Company in 1820.*** The “Norcross” in question was Joel Norcross, Emily Dickinson’s maternal grandfather, directly tying both lines of the family to Trask.

This clearly establishes a link between Trask and Norcross, but it does not definitively prove that the cotton used in these endeavors came from Trask’s plantations. But while the exact source of the cotton used in this factory is unknown, it is likely that Trask supplied it, at least while the factory was under his ownership, either through his brother and his former plantations or from his ongoing connections with Southern businessmen and politicians. When visiting his brother and his former plantations, Trask used his time in Natchez and New Orleans as a networking opportunity, documenting in his correspondence his purchase of cotton. In 1823, for example, James L. Trask wrote to Israel to inquire whether his “Cotton has been received at Boston, what the prospects are, &c.”^ Though the factory was in Wyles, Lyon, and Norcross’s possession by this point, this remark is illustrative of the personal networks necessary to operate a Northern cotton factory and suggests that he continued to be involved in the industry–perhaps even with his old factory. In this process, everyone was implicated in the system of enslavement, from the businessmen to the often-female weavers and the wearers of the eventual final product. The image of Emily Dickinson in her white dress no longer appears so ethereal as it is now weighed down by the memory of the enslaved labor that may have produced it as she began wearing it at the beginning of the Civil War.

This connection to enslavement is also apparent on Emily Dickinson’s paternal side. Samuel Fowler Dickinson, Emily’s grandfather and a founder of Amherst Academy, formed a corporation with Levi Collens, Ebenezer Mattoon, Elijah Eastman, Robert Douglas, Nathan Gilson, Asa Adams, and Samuel Perrin in 1814. The records of this factory are similarly limited as the one in Brimfield, but the 1833 McLane Report claims that the factory purchased 48,000 pounds of cotton from South Carolina per annum, and also sourced sugar and rice from Louisiana.^^ The Dickinson family’s involvement in cotton was thus not merely due to a convenient relationship with a ready supplier of cotton, but an active participation in all facets of the economy of enslavement.

Palm-Leaf Hats

The connection between the Dickinsons–and Amherst at large–and enslaved labor do not end with cotton, nor the rice and sugar likely used to feed the workers of their factories. Amherst was the largest producer of palm-leaf hats in the mid-nineteenth century, a fact that has frequently been studied in the context of outwork and the beginning of industrialization. However, little research appears to have been done on the supply chain of the palm-leaf itself. One source indicates that all of the palm-leaf in Amherst came from Cuba, who did not abolish slavery until the 1880s but was primarily involved in the sugarcane industry. Still, it seems likely that at least some of the raw material was touched by enslaved hands.

But while there is little concrete evidence that palm leaves were harvested by enslaved people, there is substantial evidence that the palm leaf hats created in Amherst were worn by enslaved people:

The hats produced by New England outworkers found their way to to the South and Midwest, where slaves, farmers, and farm laborers wore them for inexpensive protection while working outdoors. One Alabama planter’s account book, for instance, records the purchase of “12 palm leaf hats–for women” in 1843.^^^

An advertisement for an escaped enslaved man similarly includes a description of a palm-leaf hat, as does Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Like cotton (and the coarse Lowell, or negro, cloth used to clothe enslaved workers), then, the industry of palm-leaf hats is deeply interwined with the economy of enslavement. Amherst and the surrounding environs did not merely process cotton produced with enslaved labor for use in free states, but used those products to perpetuate the industry of enslavement.

But how does this connect to the Dickinsons? In Monson, about two dozen miles away from Amherst and the homeland of Emily Dickinson’s maternal relatives, Charles H. Merrick and Rufus Fay operated a palm-leaf hat factory. Fay was connected to Dickinson by way of his sister, Elizabeth “Betsy” Fay, Joel Norcross’s wife and Emily’s maternal grandmother. The wealth generated from this factory could have found its way into Dickinson’s lineage, or the industry in Amherst may have simply elevated the town’s status and afforded Dickinson access to better goods and services. Dickinson herself mentions a palm-leaf hat in “I met a King this afternoon!” as she paints a picture of a ragged man and his two sons, almost mocking his economic status as she compares them to a king and princes. How would Dickinson view enslaved men who wore the same hats?

Philanthropic Efforts

The most surface-level connection between the two families, aside from Amherst College, is the one I have already mentioned above: Emily Dickinson’s maternal grandfather, Joel Norcross, and Israel Trask both contributed to Monson Academy. Between 1825 and 1826, Trask donated $550 to the Monson Academy charity fund, the same amount he originally contributed to the Amherst College Charity Fund, while Norcross donated $1500.+ Emily Dickinson’s mother, Emily Norcross Dickinson, attended the academy with Trask’s nephew, James L. Trask, a native of the same Woodville, Mississippi, where Trask established his plantations. Either could have crossed paths with fellow student Pelleman Williams, the second known Black student to attend Amherst or even each other, perpetuating familial bonds.++

Still, this seems to be a relatively innocent connection–what is there to say about two wealthy families involving themselves in philanthropy and enrolling their children at the same institution? But, if modern discourse is to be believed, there are no good billionaires, only people who seek to cleanse their wealth and their image through philanthropic deeds. Throughout his life, Israel Trask was involved in a number of philanthropic efforts, from Monson and Amherst to foreign missions and his local church. A one-time enslaver was now a trustee of Amherst College. The prominent, philanthropic Samuel Fowler Dickinson and Joel Norcross gained at least a portion of their wealth through enslaved labor. The belle of Amherst gained at least part of her royal status through enslaved labor.

Why Does All This Matter?

Some of the above connections between Israel Trask, Emily Dickinson, and enslaved labor may appear complicated and occasionally tangential to the poet. After all, Trask died in 1835, just five years after Emily Dickinson was born. But my aim here is not to suggest that we not celebrate Dickinson because her family accumulated wealth from enslaved labor, but rather to shed light on that fact and understand her life in the context of it. The generational wealth afforded to Dickinson as a result of her relatives’ participation in the economy of enslavement afforded her the opportunity to write poetry in her large bedroom, to live beside her sister-in-law and likely lover, and for her poetry to be preserved, if not published in her lifetime. Without this wealth, would Dickinson have been forced to find a job, a husband? Would Margaret Maher, Sue Dickinson, Mabel Loomis Todd, and Thomas Wentworth Higginson have preserved her poetry, if she had the time to write it at all? Would her house still be standing, let alone be operating as a museum? Would we know her at all?

It was frequently stated to me while I was a student that what I knew was just as important as who I knew; that connections and networking were integral to finding a job after college. Joel Norcross and Samuel Fowler Dickinson operated under this same principle, working with Southern enslavers to process cotton picked with enslaved labor. Though it is true that not all of the family’s wealth can be attributed to enslaved labor–Professor Lisa Brooks has recently written about the family’s participation in the colonization of the Connecticut River Valley for The Oxford Handbook of Emily Dickinson–it certainly added to it. And while I cannot definitely state if Trask and Norcross were friends or merely businessmen operating in the same circles, the two were clearly aware of and had dealings with each other. If we remove cotton produced with enslaved labor from Emily Dickinson’s story, are we left with the same Dickinson? We are certainly not left with her clothing.

*Emily Dickinson’s Poems: As She Preserved Them, ed. Cristanne Miller (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2016), 117.

**Charles M. Hyde, Historical Celebration of the Town of Brimfield, Hampden County, Mass. (Springfield: Clark W. Bryan Company, 1879), 155.

***William T. Davis, ed., The New England States: Their Constitutional, Judicial, Educational, Commercial, Professional, and Industrial History, vol. I (Boston: D. H. Hurd & Co., 1897), 259.

^James L. Trask to Israel E. Trask, February 24, 1823, Box 1, Folder 6, Israel E. Trask Papers, Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, Amherst, MA.

^^Documents Relative to the Manufactures in the United States, vol. I, U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Executive Document No. 308 (Washington, 1833), Sugar, like cotton, also helped to fuel the economy and the North as it would export molasses and cotton fabric.

^^^Thomas Dublin, “Rural Putting-Out Work in Early Nineteenth-Century New England: Women and the Transition to Capitalism in the Countryside,” The New England Quarterly 64, no. 4 (1991): 535.

+Terms of subscription to the Charity Fund of Monson Academy, with subscriber list, 1826 November 28, Box 1, Folder 22, Israel E. Trask Papers, Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, Amherst, MA.

++Monson Academy, Catalogue of the Trustees, Instructors, and Students, During the Year Ending August 8, 1838 (Springfield: Monson Academy, 1838). Ancestry, accessed October 28, 2022.

You must be logged in to post a comment.