The Northeastern United States is home to many Indigenous communities, each with its own rich history. This guide is not an attempt to gather every resource related to learning about the Indigenous history of this area but a selection of web resources that provide an introduction and paths to additional resources.

Centering the Land

One of the key concepts in Amherst Professor Lisa Brooks’s The Common Pot: The Recovery of Native Space in the Northeast is that the Northeast, including the land now occupied by the Amherst College campus, has long been part of a very active Native network of trade and communication routes, kinship networks and seasonal travels. As is clear from the map of Wampum Trade Routes of the Northeast (below), Interstate 91 and much of the New York State Thruway system follow ancient routes established by the original inhabitants of this space and it remains a very active center of travel and trade.

This map serves as a reminder of the cultural importance of the manufacture and circulation of wampum in the Northeast and throughout Native Space. For more on the history of wampum, especially as it pertains to this region, see On the Wampum Trail and Dr. Margaret Bruchac’s essay “Native Presence in Nonotuck and Northampton.”

The Amherst College campus is situated in the homelands of the Nonotuck. In a petition to Thomas Pownall, Governor of the Province of Massachusetts, the proposed name “North wattock” (a variant of Nonotuck) was rejected in favor of naming the new town in honor of Lord Jeffery Amherst, an eighteenth-century British military leader who lives on in infamy as an early advocate for using biological warfare against Indigenous people. While the initial dispossession of land and physical removal of many Indigenous people occurred a century prior to Amherst College’s founding, this process was neither linear nor finite, reoccurring in waves over time. For example, the town chose to name itself after Amherst instead of the Nonotuck who, for millennia, stewarded this land and its natural abundance. In turn, the college named itself after the town, the effect of which was to elevate Lord Amherst to legendary heights and erase the Indigenous presence from the landscape. Notably, Jeffery Amherst never actually visited Amherst, Massachusetts.

As explained in greater detail on the Springfield-Agawam Indigenous Land Acknowledgement website, Indigenous people of this area once moved through the region seasonally, hunting, fishing, and trading along well-established routes and within expansive networks. These routes spanned the entire Kwinitekw River Valley – or, perhaps more familiarly, the Anglicanized “Connecticut” River Valley, eventually dubbed the “Pioneer Valley.” As white colonists relocated themselves to the area in the 1600s, they engaged Indigenous leaders and sought to make formal agreements with them over land delineation and shared use. Of this type of exchange, UPenn Anthropology professor, Margaret Bruchac, summarizes the engagement and outcomes:

“Native leaders likely assumed that their English trading partners would limit their new plantations [a colonial term for settlements] to small locations beside the rivers, thus avoiding interference with on-going Native activities in the broader homelands… English written promises were, however, hollow… Native people attempted, without success, to seek redress from colonial courts… In essence, the generosity of Agawam people in welcoming English colonists enabled what was, at first, a bloodless act of dispossession. Springfield’s colonial settlers efficiently moved to superimpose European boundaries and laws on Native homelands and protocols…”

(excerpted from Dr. Margaret Bruchac’s essay on the Springfield-Agawam Indigenous Land Acknowledgement website)

The fight for Indigenous rights is ongoing, nationally and internationally. In 2007, the United Nations adopted the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), with 144 states in favor, 4 votes against, and 11 abstentions; among the dissenters was the United States, who eventually reversed its vote. The UN’s website describes this declaration as “the most comprehensive international instrument on the rights of indigenous peoples,” one that “establishes a universal framework of minimum standards for the survival, dignity and well-being of the indigenous peoples of the world and it elaborates on existing human rights standards and fundamental freedoms as they apply to the specific situation of indigenous peoples.”

Suggested Readings

- Our Beloved Kin: Remapping a New History of King Philip’s War. An accompaniment to Prof. Lisa Brooks’s book Our Beloved Kin, this resource includes multiple interactive maps that trace the story of seventeenth-century colonial warfare across the New England landscape.

- Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians Out of Existence in New England by Jean O’Brien is an excellent introduction to the ways the ongoing presence of Native people has been erased from the dominant historical narrative of New England over the past 200+ years. This book is available online via JSTOR.

- For a student’s perspective on navigating the land of Amherst College, see the essay “Introduction to the Land – Where Are We?”

Resources at/affiliated with Amherst College

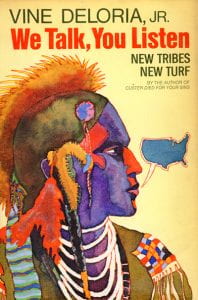

- Native American Literature Collection, Amherst College Archives & Special Collections. Amherst College is now home to a collection of more than 3,000 books written by North American Native authors ranging from the eighteenth century to the present. These items are included in the FiveCollege Library Catalog and several items have been digitized and added to Amherst College Digital Collections.

- Amherst College Digital Collections (ACDC), home to many digitized materials including some of the Native Lit collection.

- The Native American Literary Atlas, or Digital Atlas of Native American Intellectual Traditions (DANAIT), is a resource “that shares, explores, visualizes, and connects communities and researchers to the literary networks of Indigenous authorship,” and highlights books from Amherst’s Native Lit collection.

- Five College Native American and Indigenous Studies, an active collaboration among students, faculty, and staff across the Five College Consortium.

Regional Resources

- “Southern New England Native American Nations, Museums, and Organizations” Tribal communities and resources in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island.

- Native Northeast Portal. Primary source materials by, on, or about Northeast Indians. Website contains thousands of records associated with scores of Native communities from repositories around the world.

- The American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, MA hosts excellent online exhibitions featuring vital manuscripts and early printing in Indigenous languages in seventeenth-century Massachusetts: “Reclaiming Heritage: Digitizing Early Nipmuc Histories from Colonial Documents” and “From English to Algonquian: Early New England Translations.”

National Organizations

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples “The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) was adopted by the General Assembly on Thursday, 13 September 2007, by a majority of 144 states in favour, 4 votes against (Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States) and 11 abstentions (Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Burundi, Colombia, Georgia, Kenya, Nigeria, Russian Federation, Samoa and Ukraine). Years later the four countries that voted against have reversed their position and now support the UN Declaration. Today the Declaration is the most comprehensive international instrument on the rights of indigenous peoples. It establishes a universal framework of minimum standards for the survival, dignity and well-being of the indigenous peoples of the world and it elaborates on existing human rights standards and fundamental freedoms as they apply to the specific situation of indigenous peoples.”

Native American and Indigenous Studies Association (NAISA) “The Native American and Indigenous Studies Association (NAISA) is an interdisciplinary, international membership-based organization, comprised of scholars working in the fields of Native American and Indigenous Studies, broadly defined.”

The Association of Tribal Archives, Libraries, and Museums (ATALM) “The Association of Tribal Archives, Libraries, and Museums is dedicated to preserving and advancing the language, history, culture, and lifeways of indigenous peoples. On an annual basis, it offers professionally guided learning opportunities to over 2,600 tribal cultural practitioners from 352 Native Nations, as well as online training to an additional 1,432 participants.“

The American Indian Library Association (AILA). “An affiliate of the American Library Association (ALA), the American Indian Library Association is a membership action group that addresses the library-related needs of American Indians and Alaska Natives. Members are individuals and institutions interested in the development of programs to improve Indian library, cultural, and informational services in school, public, and research libraries on reservations.“

National Museum of the American Indian. “A diverse and multifaceted cultural and educational enterprise, the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) is an active and visible component of the Smithsonian Institution, the world’s largest museum complex. The NMAI cares for one of the world’s most expansive collections of Native artifacts, including objects, photographs, archives, and media covering the entire Western Hemisphere, from the Arctic Circle to Tierra del Fuego.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.